by Kevin T McEneaney

This unusual Aston Magna concert featured a double bill: Naples-born Alessandro Scarlatti’s “Humanity and Lucifer” (1704) and exiled Igor Stravinsky’s “The Soldier’s Tale” (1918). Scarlatti’s “Humanity and Lucifer” is an unpublished Oratorio which Daniel Stepner discovered in a library in Munster, Germany. Out of curiosity, he purchased a microfilm copy of the score from the library and transcribed it. He was impressed by the expert orchestration for strings, trumpet, and recorder; the score contrasted with the mostly fragmentary, sketchy, orchestration of Baroque music, which usually left orchestration to the improvisation of performers. Here the story is Mary’s opposition to the Devil, a popular medieval theme whereby Mary, cartoon-like, was often depicted as punching the Devil. The performance of this work was the first time anywhere in the past three hundred years!!!

The religious moral of the pairing was self-evident. The religious cantata was sung by ably by soprano Kristen Watson (as Humanita and Mary) and tenor Frank Kelly, who portrayed the devil with great confidence and dignity. Singing was dramatic in texture with about one-third sung in English with Stepner’s translation. The Italian language has greater verbal lyric sonority than English, yet one did not really need the printed libretto handout to follow the slim Manichean plot.

I was convinced that this unknown cantata had given John Milton the idea for his epic Paradise Lost, a beautifully composed poem, yet as the critic Samuel Johnson once judged the poem: “more a duty than a pleasure to read.” (As an English epic, I rate Milton’s poem below Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, Byron’s Don Juan, Sir John Harrington’s translation of Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, and my own epic Boldface Names.)

Scarlatti’s string lines were quite exciting, especially the magnificent vigor of Stepner’s lead violin. All nine instruments of the ensemble (with Peter Sykes’ rhythmic eloquence on harpsichord) were strictly period instruments, and it was a great pleasure to hear David Wells on the no-longer-played Buffett bassoon. At the concluding aria “Every shore and riverbank/ Replies with shouts of joy/ And sings, Mary, of your worth.”

But in Stravinksy’s A Soldier’s Tale, the devil triumphs over the hapless, naïve soldier! Here the devil appears to be an allegory of the repressive state. Instead of boasting antagonist, the devil here is the trickster of Faust legend. The devil persuades the soldier to re-enlist while trading a magic book of wealth for the soldier’s humble violin. Yet the soldier does not use the magic book to gain wealth; he returns to his home village and the village rejects him with horror because the army has pillaged his hometown. The devil appears to instruct him on the magic book.

The soldier goes into business and becomes wealthy with the assistance of the magic book. Then he realizes that wealth is emptiness and means nothing. He decides to free himself of the devil by gambling with cards, losing his wealth to the devil, and thus freeing himself. The soldier steals back his violin and tears up the magic book. The soldier courts and wins the hand of a great governor’s daughter, beating the devil for the girl’s hand in marriage. After some period of happy honeymoon, the soldier’s wife wants to see the humble village of her husband’s birth. The soldier is reluctant but concedes because he would like to see his mother once more. On the outskirts of the village, the devil is waiting for him. The devil seduces the soldier’s wife and steals back the magic violin. The hapless soldier is completely defeated.

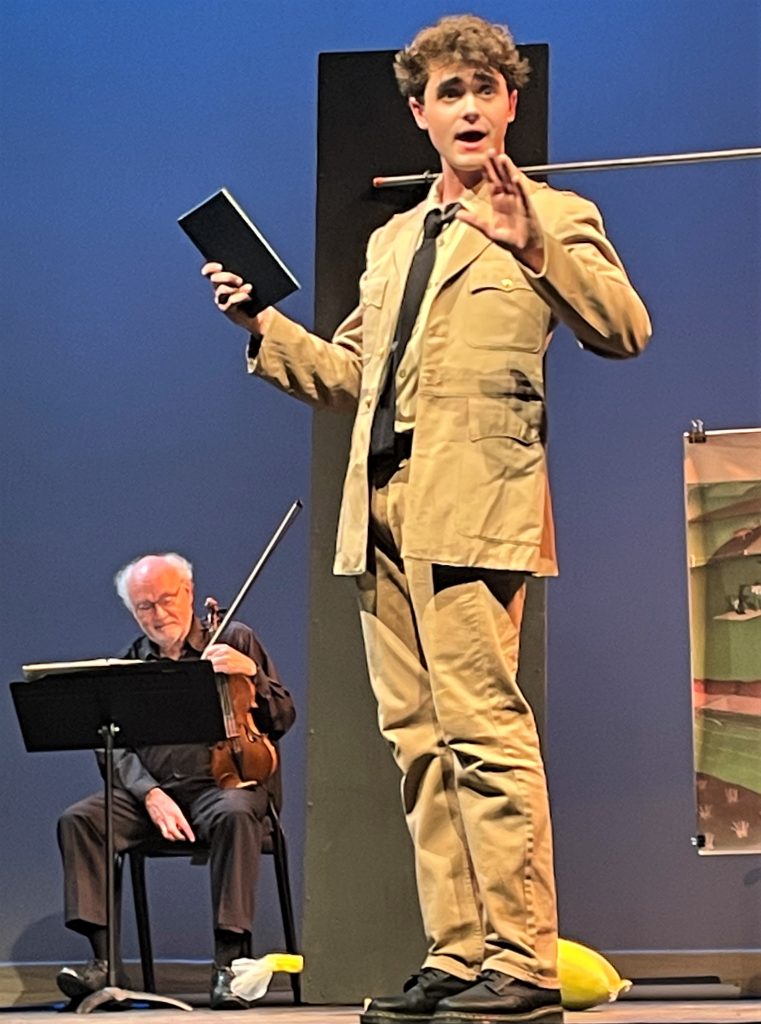

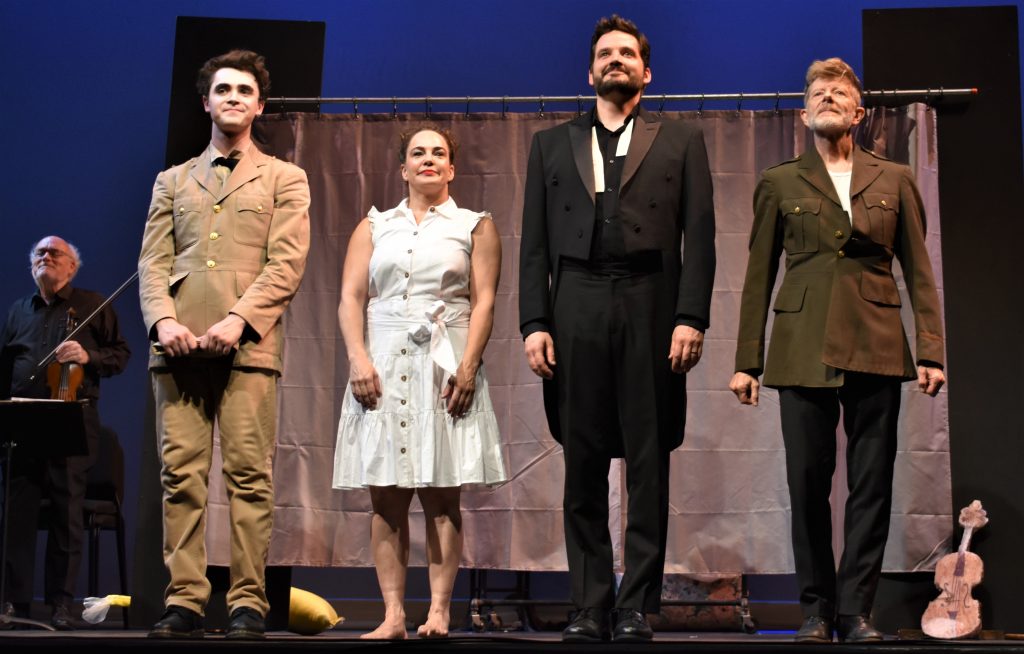

The French-language anti-war script by Swiss novelist Charles Ferdinand Ramuz was in rhyming couplets. During the recent pandemic, Stepner produced his own English verse translation, which is a superior, dramatically attuned translation. This was the premiere of that improved translation. Stepner has directed over 50 productions of L’Histoire du Soldat and this production was awesome! Frank Kelly as narrator and stage director was authoritatively eloquent with emphatically clear diction. Jack Greenberg as soldier was all-too convincing in his self-confident, innocent narcissism. David McFerrin as the devil was suave and sinister. DeAnna Pellecchia as the governor’s daughter danced up a storm.

The music has an extraordinary eclecticism: satiric marching band, tango, waltz, folk dance, ragtime, and a memorable duet between clarinet and bassoon reminiscent of passages in Stravinsky’s sensational The Rite of Spring. There is a zany, cubistic, mesmeric feel-and-appeal to this most unusual masterpiece which Stravinsky had hoped would be translated and performed in all known languages in the hope of defeating the insanity of war!

P.S. If anyone is writing a dissertation on John Milton, Daniel Stepner should be credited with the exhumation and public performance, while I should be given credit for my cogent observation: Scarlatti’s unknown librettist was the source for Milton’s inspiration when he toured Italy in 1638-39 when he must have heard Scarlatti’s cantata and others like it which presented Lucifer. Milton switched out Mary for Adam and Eve; it is the formidable character of a self-conceived, dignified, and prideful Lucifer which carries the resemblance. Being a Protestant, Milton preferred the vehicle of private meditation to public spectacle. Yes, this concert was in many ways an historic event!