by Kevin T McEneaney

Robert Schumann was enthusiastic about the invention of the French horn; love of this new valve sound which was able to play every note of the chromatic scale resulted in Concertpiece (Konzerstück) for four horns and orchestra, Op. 86 (1849). After its 1850 premiere, it was not performed for over a century due to a lack of excellent horn players. In three movements, the opening and closing movements remain robust, extroverted, exclamation marks! The buoyant optimism of this delightful piece resides in glorious fanfares that became, in retrospect, famous classics of the genre. To accompany The Orchestra Now under the direction of Dr. Leon Botstein, four French horn players from the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra were imported from NYC: Javier Gándara, Barbara Jöstlein Currie, Erik Ralske, and Hugo Valverde; they blasted and romped. The joyous clamor from this happy moment of Robert’s life with Clara presented a foil for what was to follow on the program.

Death and Transfiguration, Op.24 by Richard Strauss remains one of those sublime compositions that one can never hear enough of. Composed sixty years before his death in 1949, it appears as a meditative reflection on the course of an adventurous lifetime with meditation on childhood, young adulthood, and the wisdom of old age; it remains a luxurious melancholy ride to an Otherworld beyond the gates of life. There is such emotional depth that one is alerted to the passing nuances of life’s parade because it reaches powerful cathartic depths on the wondrous transience of life. Here The Orchestra Now played with memorable, resonant plangency. Strauss had great sense of humor, saying of his work that he was not in the first rank of musicians, yet he was the first musician of all the accomplished second rank! Yet this work remains a transfigured masterpiece, echoing in the dust of which we are composed.

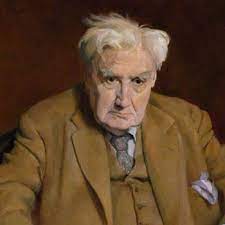

A London Symphony (Symphony No. 2) by Ralph Vaughan Williams (1913) may, in some ways, have been inspired by the first piano trio of Saint-Saëns which simulates the echo of workers at their trade and street vendors shouting wares. Williams studied under Maurice Ravel who said of Williams that he was his only student who did not sound like his teacher’s music. Like Bartok, Williams was inspired and grounded in native folk music.

The first movement dramatizes the slow rising of the sun over London with the city still asleep, then erupts with the clamor of morning rush hour and the beginning of work; the second movement takes us to noon with the harp ringing the tones of Big Ben; the third movement dramatizes the motif of work to exhaustion (here is the thematic influence of Saint-Saëns), while the last movement takes us to the afterwork pubs and theatrical shows, ending in the lament that London, as one of the greatest cities of the globe, will eventually be dust—just as Miletus, Athens, and Alexandria have lost their glory, for all great cities, like us hominids, are but dust in the end. An involuntary tear escaped my right eye, even though I only once visited London back in 1971. This is a symphony that demands more than one hearing, for it scorches the mind and emotions, producing a mostly unlikely catharsis.

Zander Grier was fabulous on tuba, Kai O’Donnell was terrific on English horn, violins and cellos were in unison, and French horns and trumpets were magnificent!

Ralph Vaughan Williams will be the topic of Bard College’s musical Summerfest. A London Symphony was but an antipasto of the banquet that is now being prepared for early August.