by Kevin T McEneaney

Like Giacomo Puccini, Luigi Boccherini (1743-1805) was born in Lucca, named after the Celtic god Lugh, the light rays of the abstract Creator (Dagda, Great Father); Luigi was named when in the womb after that god of light who married the waters of earth, Lucca being a sacred grove of Lugh. Luigi’s father was a cellist and double-bass player, while his uncle was a poet who wrote librettos for Haydn and Salieri. Luigi’s father taught him to play the cello when he was five years old. As a composer, Luigi wrote more works for the cello than any other composer. If you love the cello, then he is your man.

In 1757 Luigi went to Vienna with his father and they played for four years at the court theater, yet after his father’s death he moved to Paris with fellow violinist Filippo Manfredi in 1760 and then to Madrid a year later, eventually playing for the royal Spanish family. King Charles III objected to a passage in one of his new trios. Instead of removing the passage, he added another cello to the piece, thus inventing the cello quartet, and he was immediately dismissed. (Some aristocrats don’t have a sense of humor.) Boccherini relocated from Madrid to a small rural town in the mountains of central Spain where he remained for the rest of his life, marrying twice, and composing his most famous works while finding patronage among assorted noblemen (usually French). In 1927 his coffin was repatriated to Lucca, which holds a Boccherini festival every September.

While Boccherini was principally influenced by Haydn, it might be more pertinent to observe that Boccherini greatly influenced Haydn by calling attention to the virtues of the cello: in his early quartets the cello only accompanies, yet in Haydn’s later quartets the cello plays a more prominent role. Boccherini invented the cello string quintet (with two cellos) and wrote about 120 two-cello quintets. Many of his compositions were lost by his Parisian publisher who refused to return works that he did not publish (such scores were most likely more original, too quirky for the conservative publisher). Most of Boccherini’s patrons were French aristocrates

Boccherini is sometimes played on NPR radio, yet he is rarely played in North American performances. When the noted organist and composer Hamson Sisler received a commission to write a cello composition, he said to me “I’ve never written a cello composition before.” I replied: “Then begin by listening to Boccherini.”

Boccherini’s playful sense of humor, addressed to the populace, was on display at this concert. Boccherini can be serious, yet he remains the most humorous classical composer: impish, ironic, witty, playfully extroverted with the ability to create music that sings with seemingly effortless sheen. The title of this concert was Musica de Espana.

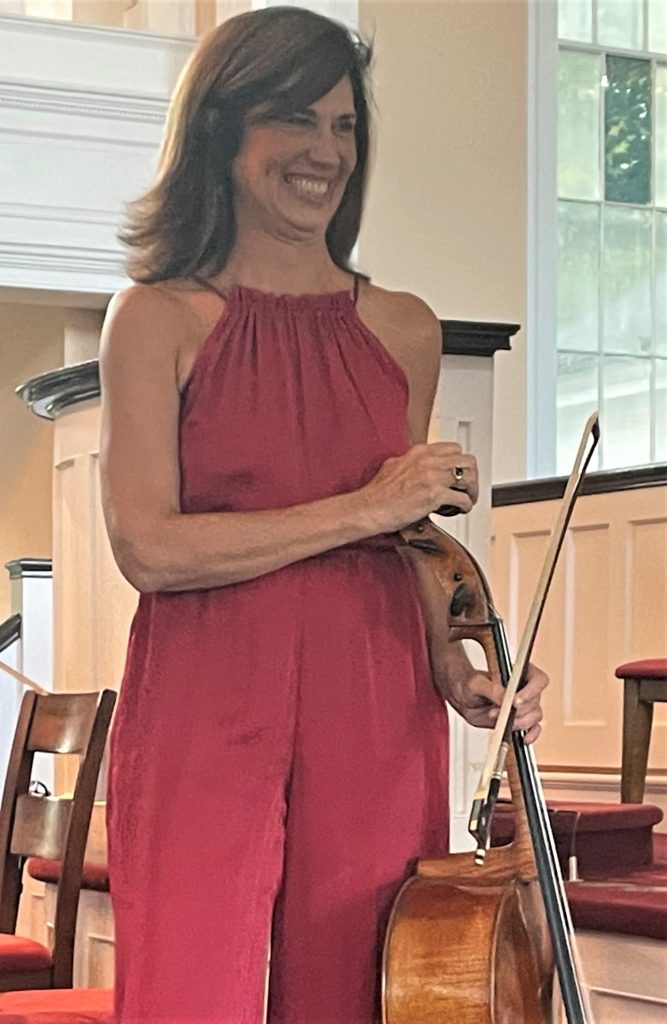

The late afternoon concert last Friday at the First Congregational Church in Washington, CT, opened with La Musica nocturna dell estrade di Madrid, seven night “scenes” at the main cathedral: the ringing of the church bells announcing the recitation of the Hail Mary prayer group with violinist Daniel Khalikov sternly leading, an amputee soldier begging with his tambourine, the dance of a blind beggar, a raucous, echoing recitation of the rosary with William Hakim’s viola excelling, a crowd ambulating outside the cathedral with Pauline Kim’s poignant violin, a drummer playing in the crowd with the cellos of Wendy Sutter and Michael Katz resounding, and robust finale of the police announcing and enforcing closing curfew.

Suite Populaire Espagnole (1914) by Manuel de Falla for cello (Wendy Sutter) and guitar (Rupert Boyd) followed. This eloquent work is similar to the Boccherini piece, painting a scene outside the Alhambra Mosque. The opening depicts veiled women weeping and walking outside the Mosque; the next movement portrays a willow tree weeping in sympathy; children dancing in the square; a mother singing a lullaby to her child; a young woman complaining that her boyfriend says that she does not love him and she replies how can you say that when I have already loved you; the portrait of an important, demanding, elderly lady. (Under Islamic law wealth is passed through the female line.) There is no seventh movement for the day of rest and prayer, yet the sequence concludes with bigotry and misogyny.

Rupert Boyd, an Australian, then played three fierce, flamenco, solo guitar works, the third piece evoking the glorious architecture of the Alhambra Mosque. Flamenco style is not native to Spain, but brought to Spain by the Roma people who migrated from Romania.

Guitar Quintet No.4 in D major, G., 448, “Fandango” by Boccherini. The opening movement is a traditional pastorale praising the beauty of the countryside hills, woodlands, meadows, and streams; the Allegro praises the architecture of cities; the Grave assai depicts a fierce tempest; the concluding Fandango depicts the repairing of the storm’s damage and concludes with festive rejoicing. In the first two movements the two cellos are played horizontally as if they were guitars (amusing satire on the vacuity of Spanish music); they come into their upright dramatic resonance for the storm and the concluding celebration, the moral of the allegory being that one can rebuild a culture with the cello, but not the guitar.

For encore, they performed String Quintet in C major in D major, 956 (1828) by Franz Schubert. Written two months before Schubert died, the work features two cellos (imitating Boccherini). Critics acclaim this work as Schubert’s finest chamber work. Despite operating in the more optimistic major, the composition evokes much pathos in the Romantic tradition of the sublime. The second cello in arrangements by Boccherini usually play in the higher register, sounding half-way between a viola and cello, yet here the two celli playing together in the lower register deliver the pathos usually found in a minor key, while the sound of the viola, poignantly played by William Hakim, is highlighted. Above all, lead violinist Daniel Khalikov was exceptional in his passionate delivery.

Next Friday, September 8th at 5:30 pm, their program is Eight Seasons, that is, Antonio Vivaldi’s Four Seasons and Astor Piazzolla’s Quatro Estaciones Portenas with featured international violinist Nicolas Danielson from Argentina. I have often wondered why I have rarely seen such plum-program, paring before.

Washington Friends of Music (WFM) organizes these concerts, website:

[email protected] will simplify the purchase of tickets.