by Kevin T McEneaney

Last Saturday’s concert opened with delightful background commentary by violinist Concertmaster Eniko Samu about the first half of the program. Grazyna Bacewicz (1909-1969) studied composition under Nadia Boulanger in Paris (1932-3). As a noted lead violinist in Poland, she experienced the tragic trauma of a car accident. Lying in a hospital bed, she realized her stage concert career would be limited, so she began composing. She became one of Poland’s most prolific composers. I am especially a fan of her astonishing string quartets.

Partita for Orchestra (1955) is a short 14-minute work, written at 46, that describes her car accident. The first slow and melancholy movement sounds like a second-by-second slow-motion visual memory of the event, then a burst of thankful survival as the second movement. The third movement languorously describes her confinement and gradual recuperation. The concluding Presto Rondo expresses great joy at her survival and that joy contains a contagious continuum, for which I was contentedly grateful.

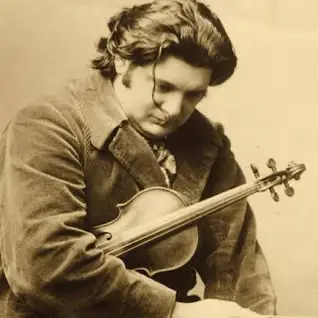

Variations for Violin and Orchestra (1879) by famous violinist Joseph Joachim, a friend of Johannes Brahms, was premiered in London (1880) and performed at Carnegie Hall (1895). The manuscript had been lost and was recently re-discovered. This concert was the second performance of this work in this country. Violin prodigy Nikita Boriso-Glebsky performed as lead violinist. Joachim often advised Brahms and Brahms also offered advice. The drama in this work positions the violin as the teacher and the orchestra as his students. The music is wonderful and exciting. yet the framing device remains stodgy and repetitive; the formula concept of the work is based upon Mozart’s Piano Concerto in E-flat Major, K.449 (1784). Nonetheless, the performance by young Nikita exceeded my expectations and the performance of the work was thrilling and memorable. There is an exciting and exuberant daring in the showmanship of the lead violin (the work was written as a showcase for what a great violinist may achieve). This was an interesting rarity that stamped the character of the concert as a whole. The unified performance of the strings proved nearly equal to the pyrotechnics of Nikita’s violin.

Concerto in D Minor (1884) by Eugene Ysaÿe (1858-1931), a Belgian friend of Debussy, Saint-Saëns, and Franck, wrote multiple violin concertos and sis well-received sonatas. This concerto was only recently discovered. In 2019 Nikita was invited to record the concerto with Orchestra Philharmonique Royal de Liège in 2019, yet this performance was the first live World Premiere of this masterpiece.

While this composition was only seventeen minutes long, its structure was lively and its destination was not predictable; the sense of time lived and breathed as more in the twentieth century than the nineteenth: it was both classical, romantic, and what the French call modern (a term that goes back to the sixteenth century, as meaning contemporary in a positive sense). Nikita once more showcased his magic violin and accompanying techniques, and I was thrilled to fall under its spell.

After Intermission the Great Mountain lay ahead, Symphony No. 2 in A Minor by George Enescu (1881-1955). Written during 1913-14, it was premiered in Bucharest on 3/28/1915. While somewhat influenced by Richard Strauss, the work is strikingly original. In three movements, the work employs more active participation of the musicians than any symphony. While the opening movement was classical, we traveled to a new world in the second and third movements which were sister and brother, Olivia Chaikin on the transverse flute offered clear piercing notes. Amelia Smerz on cello offered solid grounding. Colby Bond on clarinet was a supernatural force. The horn section provided a jubilant apocalypse.

Nearly half of the symphony is a delayed climax that is a wild thrill to inhabit. I thought of the anarchic sound of spring peepers that announce the rebirth of Dionysios, and yet beneath the rising and falling waves of ecstatic sound there appeared to be a secret Apollonian code that held and delayed the long-awaited climax, which did not disappoint when it finally arrived. The long finale constantly shifted forward and backward without resolution delivering Jacob’s multicolored robe of sound supplying an almost overwhelming experience.

The attending audience was small, yet they applauded with thrice their might, calling for more bows. Sadly, this monumental work is rarely performed.

What is the meaning of the long-delayed climax? That is an allegory of how difficult it is to attain freedom, which is a difficult trial, and in our contemporary context, this symphony offers a parallel allegory of then and now!