by Kevin T McEneaney

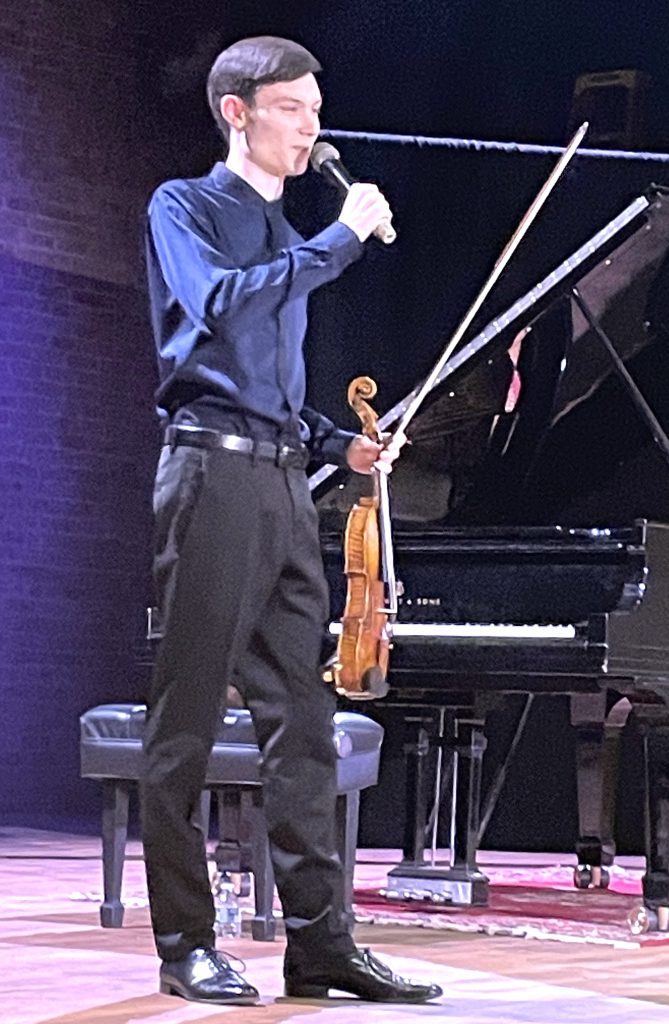

The Stissing Center in Pine Plains featured two young performers in a fascinating program of eclectic pieces chosen by 2023 Young Concert Artist Stissing Award Winner, Korean pianist Chaeyoung Park and award-winning American violinist Oliver Neubauer. Chamber Music Director Sophia Zhou introduced the two awardees.

They opened with two noted Preludes from Op. 32 by Sergey Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff, No. 5 in G Major and No. 12 in G-sharp Minor. This series of thirteen Preludes was written within sixteen days. This presentation of these piano works was arranged with violin accompaniment. Such an arrangement permitted the violin to float with a soft lyric tone over the liquid, arpeggiated keys of the energetic piano. A border edging of filigree ornamentation shared between the two instruments delivered added pleasure.

Prelude No. 12 offered a more improvisatory ambiance with vigorous, sweeping, right-hand arpeggio while the left-hand mused with languor in the melody. The second and third themes provided variations on the first bar melody. The work concluded with a gentle whisper as if the composer confessed a mysterious, intimate secret. Having the two individual winners perform together at the opening displayed their confident ability to work with other musicians. To this day these Preludes by Rachmaninoff remain prized piano pieces in home entertainment.

Chaeyoung Park then performed three Études (1915)by Claude Debussy. This series of twelve piano pieces quickly written in August was dedicated to the memory of Chopin, who established the great musical tradition of the nineteenth century; these studies provide the foundation for the twentieth-century pianistic tradition. Each study turns rigid technical limitations designed for each performance into prescient fantasies, except for Étude No. 1 which offers a satire on the mechanical piano studies of Carl Czerny, who was considered by many to be the father of nineteenth-century pianistic technique. Titled “Pour les cinq doigts,” this shocking, explosive clattering mocks the pianistic exercises recommended by the German-born Czerny. Park performed the work with biting exuberance while ridiculing the absurd rigidity of Czerny’s recommended techniques. Her bravura, biting performance evoked astonishment.

Étude No. 5, “Pour les octaves” offered a poetic, lyrical, liquid ambiance that still lingers in my mind as a joyous treasure illuminating the run and rush of water as if it were the rhythm of blood running through my brain. I will never forget this marvelous feat of incarnate magic and mystery. Étude No. 6, “Pour les huit doigts” meant that one could not use one’s thumbs in this lively yet often slow mediation on the mysteries of Nature, the god whom Debussy worshiped. The sudden elegant changes in octaves sounded with casual intuitive ease. This was a superior exercise for four digits, instead of the usual five, although the best students of Debussy vigorously complained about not using their thumbs; he reluctantly relented and said that they could use their thumbs, yet he never changed the title. The audience roared with jubilant excitement and demanded a second bow to conclude the first half of this extraordinary concert.

Florida-born Ellen Taffee Zwillich (b, 1939) was the first female composer to win the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 1983 for her first symphony; she was also the first woman to earn a doctorate in music from the Juilliard School and has subsequently received six honorary doctorates.

For this second half of the program, Oliver Neubauer was loaned a 1725 “Milstein” Guarneri Del Gesù violin. The six-minute Fantasy for Solo Violin by Zwillich remains one of her most famous works. Oliver studied this work under Zwillich. The work is notable for its flexible interpretation and one can listen to myriad versions, including various cultural slants, on the internet. The piece begins with a classical thrust, then shifts to permutations: a plethora of musical styles including jazz, Appalachian folk music, and Asian music, then ending with an Appalachian riff. This glittering gem shined with luster on the resonant Guarani on the shoulders of Neubauer. (I wished he would pay it again!)

Park rejoined Neubauer for a performance of Violin Sonata in E-flat major, Op. 18 (1887) by Richard Strauss. While in the traditional three-part classical format, the work is Romantically autobiographical. Opening with a solo piano introduction, the violin appears to be melancholy and extremely lonely, in search of a companion, yet oblivious to the piano whom he finally notices and begins to converse with, which cheers the violin up.

The second movement triggers a recollection of childhood: his mother, games played, and his youthful introduction to music. The charge of happiness in recalling childhood presents a mood of spontaneous improvisation, which is often the trademark of a gifted child. The naïve plonking and tinkling of the piano are memorable as the piano dramatizes the simple joy of becoming aware of music.

The Finale third movement remains famous for its “mountains.” This is not a fundamentalist praise of Alpine scenery, but an excited allegory for mountains of joyous love, for in that summer of 1887 Strauss met the opera singer Pauline de Ahna, two years his elder, and they were eventually married seven years later.

The concert opened by posing the question of whether these two different and particular instruments might get along, concluding that such an arrangement is the perfect arrangement: we all will have a joyous life if we can discover a way to get along and love each other in “mountains” of joy!