by Kevin T McEneaney

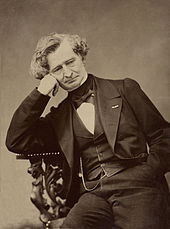

This year SummerScape at Bard College has its focus on Hector Berlioz and the Romantic context of his period. The music of Berlioz may be characterized as aiming for sophisticated popularity. Berlioz had participated in band and choir music, noticing that a large choir of average singers could be superb; he transferred that idea to the orchestra; he originally wanted 200 mediocre string players in the orchestra for his Symphonie Fantastique, yet had to settle for 130 at the premiere, which was a disaster. Liszt and Berlioz were the great champions of program music that could rise to mountainous heights.

It has been observed that Berlioz had a trinity of the intellect: Shakespeare, Goethe, and Virgil. It might be said that his musical trinity was Beethoven, Gluck, and Rossini. Berlioz noted that Beethoven occasionally employed both Major and Minor keys in his quartets, something forbidden in French music. Berlioz was determined to put his dramatic Romantic stamp on French music using that difficult technique; he managed to do this, and that struggle is described in detail in The Memoirs of Hector Berlioz (1870), which is predominantly a catalogue of his wounds and frustrations which could be subtitled as My War Against the Philistines. While obsessively narcissistic, Berlioz was an excellent psychologist, and his dissection of other’s people’s flaws can be extravagantly satiric and amusing, although the cavalcade pageant becomes tiresome.

Last Saturday night’s concert at Bard’s Sosnoff Theater opened with Gluck’s Overture to Iphigenia in Aulis (1773) in Wagner’s slightly improved arrangement (1847) with the TŌN orchestra under the baton of Dr. Leon Botstein. Then it was the Hymne des Marseillais in the 1830 arrangement by Berlioz. With the orchestra at full strength, the walls and roof of the theater underwent a sound-stress test. This was the complete orchestral version, which few Americans have ever heard: it was pulsating, divine thunder! No one in the theater that night could ever forget this experience!

Three movements from the exceptionally lengthy Les Troyens (1856-58) were played: the rhythmic Trojan March, Nuit d’ivresse et d’extase, infinite, and Royal Hunt and Storm. That ecstasy possessed transcendent elements, and the storm was pleasantly dramatic. Tenor Joshua Blue sang forcefully with power and sparkling diction and dignity while mezzo-soprano Megan Moore sang with explosive, expressive ardor.

I presume that the Overture to Fra Diavolo by Daniel Auber (1830) was an interesting period sampling foil to set up the glory of Berlioz’ Te Deum, Op. 22 (1849) where the Bard Festival Chorale under the masterful direction of Jame Bagwell delivered let loose its magisterial thunder of a hundred voices. In this religious meditation, I was especially moved by the Angelic Hymn. The Te Deum in its early draft of 1843 featured the first orchestral appearance of the saxophone (invented by Adolphe Sax).

There is popular public, grand majesty in many compositions by Berlioz, an expressive and powerful dignity with deep, warm emotion that is lacking in English music (apart from Purcell, Handel, and perhaps Britten).

This SummerScape is an ongoing event that features many unusual period pieces from Schumann to Mendelssohn, and many others. The peril of discovering something new awaits the avid concert attendee!