Last Sunday, the New York Philharmonic String Quartet, in the Clarion Concert series, delivered a memorable performance at The Stissing Center in Pine Plains. They opened with String Quartet in G major, Op. No. 1 HobIII:81 by Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809). Haydn had invented the quartet format; by 1799 it had blossomed beyond Vienna and became the most popular musical format. That year Haydn composed his last quartet, a series of three, of which only the first of the three had been finished. We do not know for sure for whom these three quartets were written, yet I think it was composed for the court of Prince Lobkowitz.

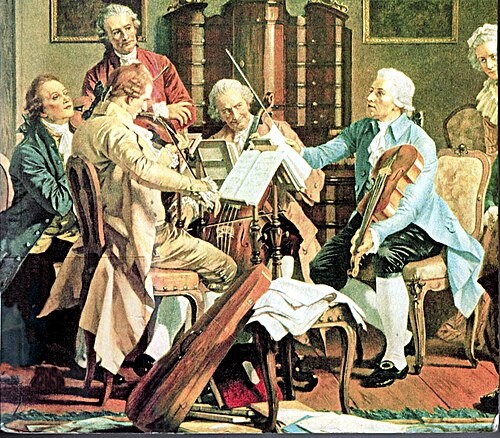

This late quartet resembles in motif and format String Quartet Op. 20, #3 in G minor, a lively, witty dinner conversation between four intelligent men discussing social affairs. This early quartet was written for Prince Nikolaus Esterházy. The outer movements of the instruments offer an elliptical structure that enhances spontaneous humor as each instrument-personality participates in vigorous repartee. My interpretation of Op. 20 #3 is that this represents a court dinner.

At the table sit the Prince (first violin) and his wife, Marie Elisabeth Ungnad von Weißenwolff (second violin) with the Treasurer (cello) and his wife (viola). The prince speaks of possible extravagant projects and feasts with added suggestions by Marie, while the Treasurer replies with the estimated cost of these projects with a sense of humor. The cello checks the fantasies of the Prince with reality—the cello is the dominant player because it is grounded in reality, not tempted by the grandiose indulgences of the Prince.

In Op. 77, No.1, composed for a London audience there are similar motifs. The opening Allegro moderato is the peasant movement. The intense march mimics the preparation for the banquet: cleaning the hall, putting out plates, silverware, napkins, flowers, and the preparation of various foods in the kitchen. The Adagio dramatizes the polite conversation between the King (first violin), his wife (viola), and another august and terse personage (cello), and his wife (second violin). The conversation appears genial with the King dominating conversational dialogue. The Minuet depicts many dancers while the Presto depicts three talented dancers, two men and one woman dancing with both men, who display marvelous footwork. The Finale depicts the revelers walking in the evening, enjoying the wonders of Nature on the estate, which are superlative to the indoor entertainment. The Presto offers a dramatic painting of creeping dusk, and here the violin of Concertmaster Frank Huang delineated such sumptuous lyricism on the violin that I will never forget that musical sunset!

String Quartet No. 1 in G Major (1929) by Florence Price (1887-1953) was likewise a marvel. Her compositions possess a distinctive classical style and ambiance; her tone is confident, curious, and warm. After the recent discovery of hundreds of her non-published manuscripts, her life’s work is undergoing a remarkable revival. Her work blends classicism with romanticism, spirituals, and the blues.

I surmise that this composition is a series of memory slides. The opening Allegro offers a recollection of young adulthood immersed in a lengthy stroll along a riverbank with an appreciation of myriad vegetation and trees amid the innocence of youth. Carter Brey’s cello grounded this excursion with delicate delight. Qianqian Li on second violin provided a sweet empathetic tone that enhanced the excursion.

The second movement was divided into two parts. The Allegro appeared to depict a man and woman in dialogue that culminated in an angry public argument, the first violin being the man and the viola being the woman. As the voice of Price, Cynthia Phelps possessed heightened anger as her bow became a blur of fast high notes all ironically presented with a waltzing theme. What a magnificent role, and here was a performance on the viola to astonish both ear and eye! Perhaps this was a depiction of Price’s divorce….

The concluding Allegretto sounded to me like a treasured recollection of love that contained suspense with culminating sexual happiness and calm satisfaction. This unconventional reversal was a wondrous surprise to revel in a splendid musical, autobiographical presentation. A recent biography, The Heart of a Woman, was published by Rae Linda Brown with the University of Illinois Press.

After a brief intermission, they performed Antonín Dvořák’s great String Quartet No. 11 in C Major, Op. 61, B.121. Written in two weeks during the later part of 1881, this remains Dvořák’s most polished and concise quartet that features cyclic motifs which are recycled with surprise tweaking, thus avoiding repetition while it runs for a little over 45 minutes with ingenuous thematic twists. The first performance was given in 1882 by the Joachim Quartet in Berlin.

The opening is as suspenseful as it is startling. Major-minor oscillation dominates the first movement. The second movement meditates on spiritual aspects of life amid a broad cantilena. The Scherzo was jaunty with strong classical lines. The fourth movement has an intricate, dense texture with a plethora of related themes which is hypnotic with resolution. The whole composition is drenched in poetic lyricism. These four players were so welded together in mystic synchronicity as they played that their unity appeared to be a model of transcendence.

The audience erupted in applause, having experienced a strange, luminous sense of being reborn by musicians from a mysterious Otherworld.