by Kevin T McEneaney

Last weekend, under the baton of Dr. Leon Botstein, The Orchestra Now (TŌN) offered an unusual program of rarely performed music that focused on Ukrainian themes. They opened with Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s Overture on Russian Themes, Op.28 (1866, revised in 1880). Rimsky-Korsakov, an ardent disciple of Miliy Balakirev, attempted to characterize melodic elements that defined the scope of Russian music. That was a bit like putting a bureaucratic seal of approval on certain strains of folk music east of Moscow.

Russians claim that Ukraine is a part of Russia (the great medieval city of Kiev long preceded the rise of Moscow, which means field of flies. Russians don’t acknowledge the existence of Ukrainian folk or classical music compositions. If a motif from Ukrainian folk music is employed by a Russian composer, it is declared as being of gypsy origin. Russian music critics like the late great Richard Taruskin never mention or write about Ukrainian composers. There is only one serious book in English available on Ukrainian music: Ukrainian Musical Elements in Classical Music by Yakov Soroker, Andrii Hornjatkevye, and Olya Samilenko (1995), although many books on Ukrainian folk music are available.

The influence of Rimsky-Korsakov was immense upon subsequent Russian composers, yet orthodoxy remains a stern byproduct of hypocrisy. The Overture delivers an emphasis on flute (where Youbeen Cho was marvelous), oboe (where Nathalie Graciela Vela excelled), and clarinet (where Craig Swink was outstanding). Zack Grass on tuba was hauntingly memorable. This presentation of Russian Orthodoxy offered a foil for subsequent comparison in the concert.

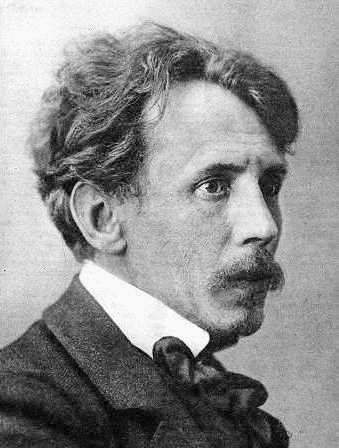

Ĉiurloinis’s in the Forest (Miske) (Every Monday cats in the forest) by Mikalojus Konstantinas (1875-1911, born in Lithuania), written at the age of 25, provides a mystical forest landscape of shadow, twilight, moonlight, and starlight. He often made his living as a choir conductor and is principally known as an important impressionistic painter. His music excels at tone correspondences and gentle, dreamy, enchanting rhythms. Once more, flute and woodwinds dominated with a mystical undercurrent from a chorus of eight cellos. This was a strange opus that delivered indescribable emotions about a forest landscape and mood with gentle, whispering percussion.

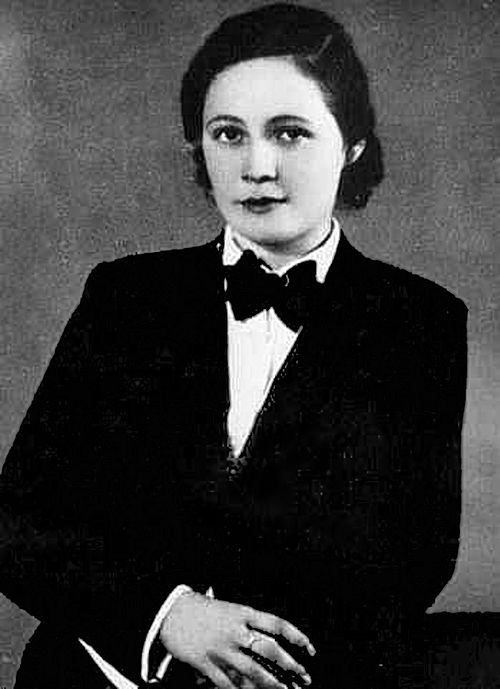

Military Sinfonietta, Op. 11 (1937) by Vitĕzslava Kaprálova (1915-1940), a student of Bohuslav Martinü, born in what is now the Czech Republic, wrote about two dozen well-received compositions and died in exile in France at the age of twenty-five, dramatized the coming horror of World War II with menacing horns and frightening percussion. Her prophecy before the event of war offers a chilling premonition. Horns under Jack Sindall delivered a shudder to the spine. Violins under Concertmaster Luca Sakon emitted an arresting, whirling warning. Percussion by Philip Drembus was thrilling as my ears trembled.

Festival Coronation March (1883) by Peter Il’iych Tchaikovsky offered an example of praising a Russian ruler who was a patron. Although this composition of five minutes remains an impressive fanfare with horns blazing, Tchaikovsky had a hard time writing the work. Emperor Alexander III was known as The Peacemaker and a significant patron of the arts, yet he initiated conservative anti-liberal reforms while making an alliance with France against Germany. This march contains a magnificent, rousing conclusion of soaring horns with superb percussion.

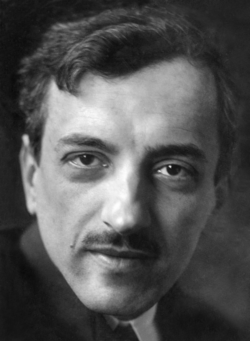

The highlight climax of this concert was provided by Symphony No. 3 “Peace Shall Defeat War” (1951) by Boris Liatoshynsky (1895-1968), which runs for forty-five minutes. The first bellicose movement was a denunciation of past wars. While the first movement appears to be influenced by Shostakovich, the second, more lyrical movement, shows the influence of Charles Gounod’s Symphonie No. 1 in D. The fierce crescendo of the third movement is deeply memorable. The final long Allegro is fast and furious, with an impressive undercurrent of eight sawing cellos under Principal Cellist Hannah Brown. Percussion under Nick Goodson offered an apocalyptic metaphor for nuclear destruction of the planet. The intensity reminded me of Symphony No. 2 in A Minor by George Enescu (1914). This underperformed symphony should travel the orchestral auditoriums of the world!