by Kevin T McEneaney

Rebecca Clarke’s Morpheus (1917) for piano and viola may not be familiar to many concert attendees today, yet during Clarke’s lifetime, it was a well-known concert piece performed at Carnegie Hall in 1918. (Its first performance was at Aeolian Hall.) An impressionistic work influenced by Claude Debussy and Morpheus remains an important chamber work and its selection for this concert of difficult works to play added to the excitement of expanded horizons. Clarke, a world-renowned virtuoso viola player.

While a successful public performer and composer, her compositions were sporadic. Although Clarke was born with American citizenship and lived much of her life in the U.S. , she does not usually appear in books about U.S. music history, which is a serious omission. For reliable information go to: https://rebeccaclarkecomposer.com/music/

Morpheus was the Greek god of dreams. A musical soundscape of dreams, as in French impressionist paintings, floats in molten aerial aesthetic with sumptuous subtle harmonies. On viola Milena Pájaro-Van De Stadt performed a few difficult passages while on piano Anna Polonsky conjured a range of moods from happy to fierce, yet it was the viola that was in the end both more fragile as well as fierce.

Piano Quartet No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 15 (1879) by Gabriel Fauré, who had his own distinctive, late Romantic sound, offers autobiographical musings as improvised diary jottings amid redolent reverie. The opening Allegro in sonata form appears to question, playfully, the form itself. The opening dotted rhythms of the Scherzo declaim the composer’s freedom of the heart to wander at will with form. The somber Adagio, where Sharon Robinson excelled on cello, laments the recent death of his father and Polonsky evoked deep emotional texture here. The concluding Allegro molto offers a joyous reversal in domestic celebration of wife, children, and friends with a brief recollection of Faure’s first musical fascination, the ringing of rural church bells. Jamie Laredo’s violin filled the auditorium with happiness. The spontaneous intimacy of the piece delivers contagious delight.

As the second half was about to begin, a strange new instrument was brought on stage in a zipped leather case. Unzipped, it turned out to be a bottle of champagne to tempt the Quartet to play with high-octane bubbling notes.

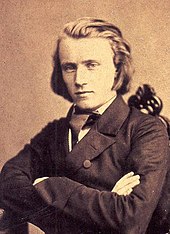

Now to the great mountain. I have a stack of books on Brahms which offer interesting technical observations on the intricacies of Piano Quartet No. 2 in A Major (1861) by Johannes Brahms. I am a music appreciator, a poet, rather than a musician. No one appears to know what this august, impressive masterpiece is about, so I will toss-in my middle-brow two cents.

This four-part quartet paints the seasons; it is a Romantic updating of Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons (1719). The long opening Allegro non troppo delineates the amazing fruits of golden autumn. The shockingly somber, Poco adagio bemoans (with cello) the harshness of winter. The Scherzo announces the wondrous rebirth of flowers and trees with lightening arpeggios at Polonsky’s fingertips as rain falls on the house roof. The Finale Allegro with its rural fiddle folk tune celebrates the ariel season when music itself dominates the intoxicating landscape of longer days and people (Presto) dance to the music. Once more Laredo’s violin sang robustly; this time, with earthy clarity.

I think Edvard Grieg studied Brahms Piano Quartet No. 2 quite closely in Leipzig; he returned to Norway to compose his accomplished Violin Sonata No. 2 (1867), which also charts the four seasons in four parts with slight autobiographical inflection.