by Kevin T McEneaney

Sterling Elliot has the press nomenclature (as a 2021 Avery Fisher Grant winner) of being a rising star, however, that is not correct: he is a star cellist who has risen beyond hopeful promise to astonishing maturity. If you see his name on an upcoming venue, take the leap, and hear what he is up to, no matter what the program offers.

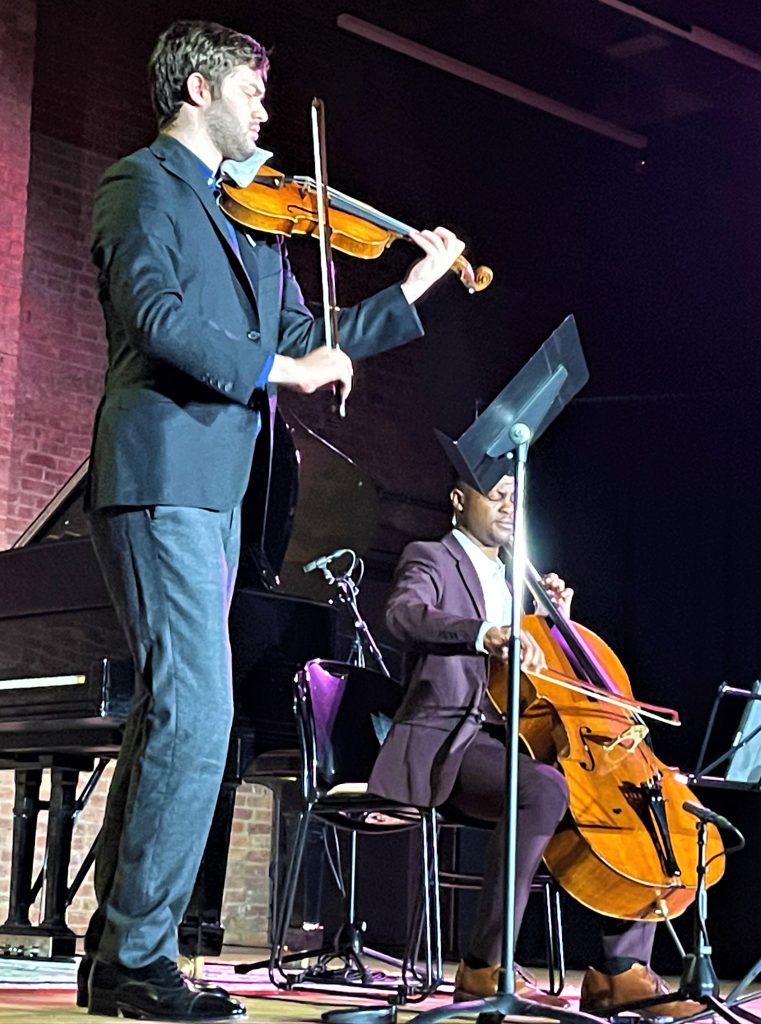

The opening program Sunday night at The Stissing Center in Paine Plains featured Duo for Violin and Cello (2015) by contemporary American composer Jesse Montgomery. The program said this work was an ode to friendship, yet I heard a different perspective ensconced in autobiography. The work opens with joyous memories of childhood, Appalachian, fiddle tunes which fiddler Nathan Meltzer was completely at home with, then swings to sophisticated jazz improvisation which was an exciting segue dramatizing Montgomery’s evolution in music before it turns to Phillip Glass-like serial composition. While Montgomery’s cellist friend (to whom the work was dedicated) was honored, it was Sterling Elliot who transported the work into transcendence. The river of sound that kept the swift current alive was Sophia Zhou, Director of the Chamber Music Program at The Stissing Center, on a sparkling run of fluent piano keys at the Baby Grand Steinway, the river on which the cello floated.

Sonata in G minor for Cello and Piano, Op. 19 by Sergei Rachmaninoff (1901) followed. While Rachmaninoff did not possess the broad sociological vision of Tchaikovsky, he possessed gifted lyricism. This work was designed to show off the cello, however, the inspirational leads are by the piano (Rachmaninoff was, after all, a great pianist). While Sophia Zhou lead with authority and liquid panache, Sterling Elliot on cello so-excelled with unity, it sounded like the two instruments were but one instrument abolishing previous performances. Most notable in this performance was the moody roller-coaster of emotion that left the listener at the edge of seat. How could such turbulence be digested? Yet there was not even time for that question, as the chameleon keys under Zhou’s fingers were off to the next theme before one could comprehend what one just heard, and the cello wanted to suggest new directions for which there was no time to explore. In four movements, this was a breathtaking, rapid, modernistic slideshow of what abundant inspiration the keyboard was able to achieve with the cello challenging that achievement with diverse suggestions of improvised follow-up.

Trio for Piano, Violin, and Cello (1914) by Maurice Ravel was composed in the French Basque commune of Saint-Jean-de-Luz. Ravel was a brilliant, impressionistic composer who was mentally bipolar, yet able to transform the conflicting agon in his mind into great musical drama; in this case, the Apollonian serenity of idyllic landscape versus the varied possibilities of sensual ecstasy with bravura fortissimo fanfares from piano amid the Siren trills of Meltzer’s violin and Eliot’s seemingly spontaneous, practical acquiescence, the cello being an integral temptation of erotic landscape to be repressed. The violin sings of temptation, while the cello earthy grunts degrees of satisfaction, yet in the end resolution, the Dionysian temptation is overcome by Apollonian, idyllic solitude. And before that happens, the path to arrive at conclusion appears to consider every sensual possibility that a cello might summon. The cyclic motifs of the piano confirm our mortality. This magnificent work was written on the eve of the First World War.

One departed with a sense of not only elevation, but of disorientation….