by Kevin T McEneaney

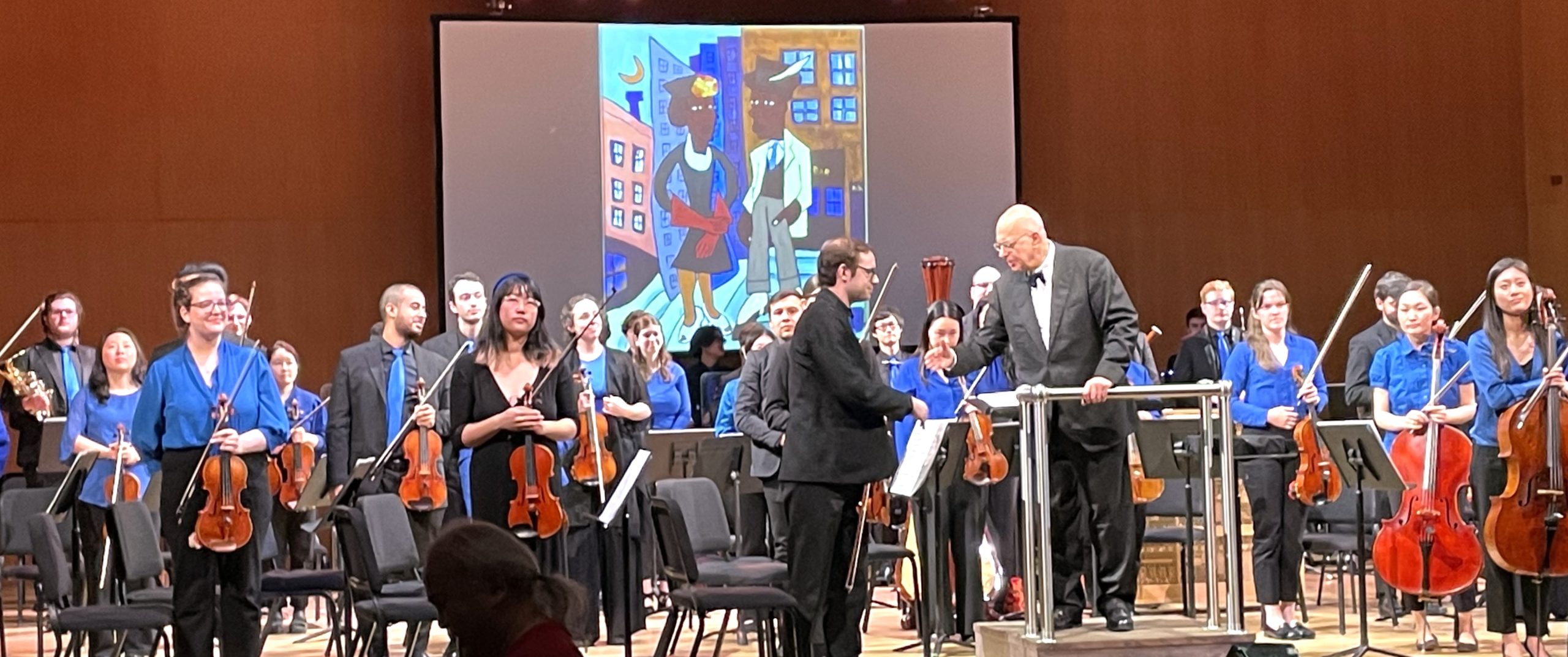

In connection wih the new Harlem Renaissance exhibit the New York City Metropolitan Museum featured in their auditorium a performance of the first Symphony (nicknamed the Afro-American Symphony) by William Grant Still. This performance was preceded by a fifteen-minute Welcome and Orientation Lecture by Denise Murrell, the curator of this Harlem Renaissance exhibit.

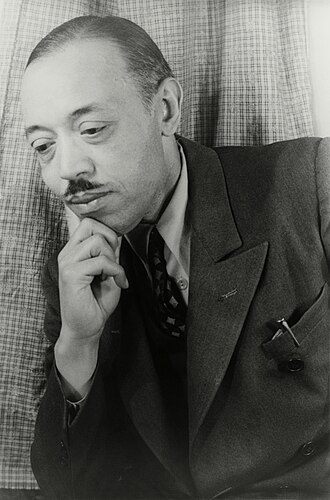

William Grant Still remains the first important Afro-American classical composer. Unfortunately, his work is rarely performed. I first heard his piano concerto Dismal Swamp (1935) performed at Bard College’s Sosnoff Theater on May 11, 2022. I was impressed by the sophistication of the composition: its ethereal beauty offered an impressionistic mood work which made me think of the large, tableau, water-lily paintings of Claude Monet. I was delighted by the intersection of painting and music, as well as the conversation of the piano with orchestra.

One of the pleasant and dynamic signatures of The Harlem Renaissance was the intersection of music, painting, and poetry; such was present in Still’s first symphony which runs for twenty-five minutes. Dr. Leon Botstein presented an hour-long lecture of this first symphony, pointing out the architecture, orchestration, and symbolism of several movements with Bard’s The Orchestra Now playing snippets. This composition was heavily influenced by social developments in the arts, as well as several poems by Paul Lawrence Dunbar. Botstein pointed out that Still’s compositional style incorporated cultural ethnic earmarks in much the same way that Smetana did for his native Czechoslovakia and Bartok did likewise

After Intermission, the orchestra performed Still’s Symphony No. 2, Song of a New Race (1937), the same year in which Samuel Barber performed his First Essay for Orchestra, Op. 12.

Dr. Botstein then conducted Still’s thirty-five-minute Second Symphony which opened with evocation of rural farming and rural landscape, perhaps somewhat influenced by Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6, Pastoral. Here the strings with Concertmaster Jonathan Fenwick, accompanied by Cheng (Ashley) Wei on harp, dominated the first movement, then there was a short break after the first movement. The second movement appeared to chart small town social life of African Americans, then transitioned to swing and jazz in big cities, charting the rise of a new musical sophistication.

There was no break between the second and third movements. Here the orchestra’s clear, sharp horns were magnificent (yet out of sight on the small stage); Quinton Bodnár-Smith on oboe provided eloquence. (Still was a noted oboe player for many orchestras.) The symphony concluded with optimism that this process of African American cultural evolution would arrive at more social and artistic prominence as well as international recognition, the goal of the Harlem Renaissance.

William Grant Still was born at Woodville, Mississippi, in 1895. His father was a musician who taught music at Alabama A&M College, yet died when William was an infant; his mother, a schoolteacher, moved to Little Rock, Arkansas. He graduated from Oberlin College and went on to the New England Conservatory, studying under Chadwick and Varese. Still received three Guggenheim fellowships; he wrote five symphonies, four ballets, nine operas, much Hollywood film music. Some of his work was performed in Europe.

In 1936 Still became the first African American conductor of a major orchestra, the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Still’s opera Troubled Island (about Haiti) was the first African American opera performed by a major company in 1949 (although written a decade earlier). His opera Bayou Legend (1949) was the first African American opera ever televised (by PBS).

The year before Still died in 1978, the William Grant Still Arts Center opened in Los Angeles. In 1999 Still was inducted into the American Classical Music Hall of Fame.