by Kevin T McEneaney

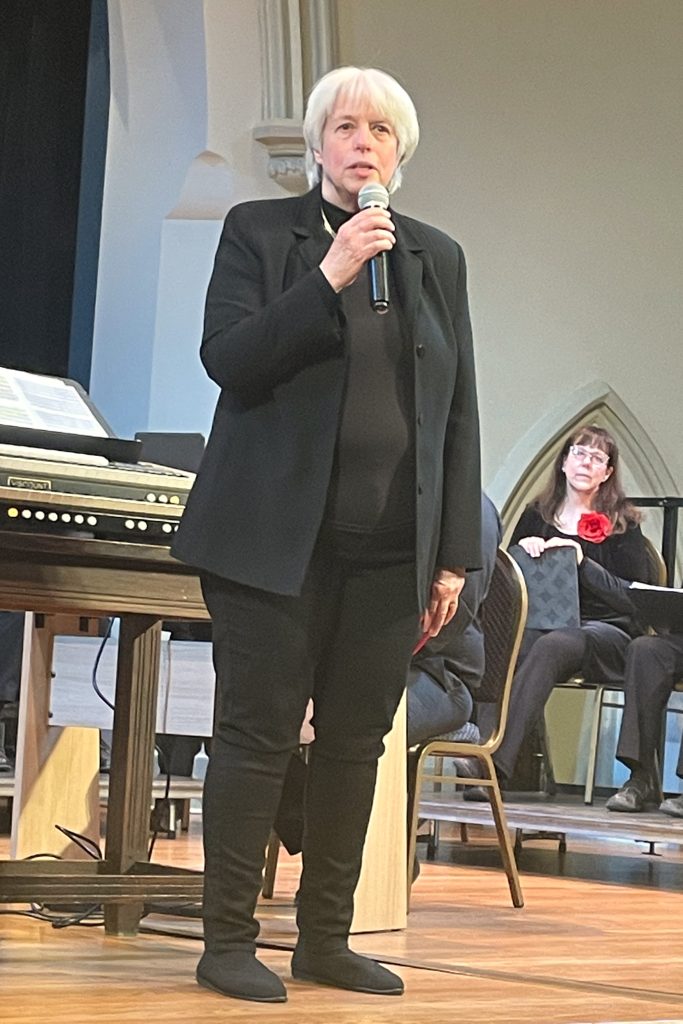

This past Sunday at Saint James Place in Great Barrington, Crescendo offered a choral presentation, predominantly by female authors who are not well-known. The program, under the direction of Christine Gevert, was titled Revolutionary Renaissance: Motets and Madrigals by Groundbreaking Composers of the 1500s.

The opening madrigal for four mixed voices was a two-stanza lyric by Maddalena Casulana that employed word painting technique whereby high happy notes ascend in a flurry and melancholy notes were slow descending with dissonance. The first stanza was about happy rural love, while the second was a shocking and arresting meditation on death. Lead singer Soprano Jennifer Tyo Oberto exulted in the rendition with clarity and emotion.

Another Italian madrigal by Casulana entertained a complicated pun on sun and son adorned with astonishing assonance. Another short yet intense madrigal on love acclaimed love to be immortal, yet acknowledged death, ending in io, meaning also, but in Greek io is the celebratory wedding cry of joyous union!

The concert employed a minimum of musicians: organ console Juan Andrés Mesa, who delineated rhythm, and Christina Patton, Director of the Baroque Opera Workshop at Queens College, on harp and recorder, excelling impressively on both instruments.

A similar ironic freighting paradox appeared in a short madrigal by Isabella Medici. Lucia Quinciani provided the first known solo monody composed by a woman, a brief complaint ending with a lady being crueler than hell.

Three works by Vincente Lusitano, a dark-skinned composer from Portugal who was active in Spain and Italy, followed. Late in life, Josquin Des Pres invented four-part polyphony at the cathedral of Notre Dame. (His sarcophagus was discovered during the renovation of the cathedral, yet not a single sample of his work was performed at the recent re-opening concert at the cathedral.) A three-voice madrigal about the last rose of autumn delivered a single elegant sentence with the flow of a gurgling stream.

Casulana’s five-voice madrigal, recently discovered in a Moscow library, offered praise of a nobleman from Verona with pleasant open vowels.

A six-voice Salve Regina motet by Lusitano featured a solemn elongation of notes with overlapping plainchant polyphonic melody that deliverd a memorable conclusion with emphasis on long-letter sounds. A four-note dropping melody motif is repeated 141 times! The lyrics and sound quality were far superior to most versions of this well-known song. Lusitano became a Lutheran and traveled north to Germany, applying for a court position, which he did not get. Since he was vastly overqualified, historians wonder whether it was his dark skin or lack of German language that resulted in not receiving the position.

After a break, three short double-choir motets (published in Venice, 1593) by Raffaella Aleotti were performed. The third motet, based on lines from The Song of Solomon about the blossoming of love in late summer, delivered a delightful aesthetic of love.

Three vigorous motets by Lusitano followed, where tenor Igor Ferreira’s voice exploded with impressive sonority. The masterful Finale was based upon a motet by Josquin des Pres where Lusitano expanded Josquin’s five voices to eight amid a plainchant cannon, which supplied an astonishing and spellbinding aura.

This concert was about all the choral singers being on the same page (note). Soprano Jennifer Tyo Oberto, Sarah Fay, and Laura Evans were outstanding amid the choir, yet it was the unified voice of the choir that sculpted in air a memorable event under the direction of Christine Gevert.

The sixteenth century in Italy enjoyed a remarkable efflorescence of music, painting, and literature sponsored by an educated and sophisticated nobility endowed with remarkable good taste.