After Salman Rushdie’s lecture on composing his his novel Quichotte (the proper period pronunciation is in the title, before the royal lisp was adopted) at Bard College Sosnoff Theater, I went backstage, chatted with him; he was open, amusing, his personality exuding a remarkable generosity and scintillating intelligence. This particular novel stands as a great masterpiece of literature. Since many writers are hoping that Rushdie will survive with his outstanding gifts, I reprint this TMI article from September, 2019.–Kevin T. McEneaney

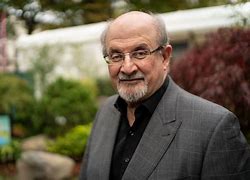

There is more than one Quichotte in this world: There is the Don Q of parts one and two of the novel that banners his name, the Q of the plagiarized sequel to Cervantes’ part one, and now the Quichotte of novelist Salman Rushdie, who has set his new epic satire in a passage not to India but to the United States from Bombay via London. The real living Quichotte was on stage at Bard College’s Sosnoff Theater under the simulating pretense that he was Salman Rushdie, a prodigious reader and scribbler who carries the classics of world literature in his portable three-pound brain. There he was on stage: affable, unpretentious, behaving like a was a real person who just happened to be a writer who had no idea of what he might write next.

Yet it was what he had most recently written, Quichotte, which is why hundreds were gathered to buy the new novel and hear what this Hercules of prose had to say. There were two parts to this event: the formal televised conversation with Joe Donahue of WAMC and the off-the-cuff informal chat with Rushdie after the filming was finished. Dick Hermans of Oblong Books was there to deliver the second half of the ticket: the hard copy of Quichotte.

Since I’m not sure everyone knows what a quichotte is, or was in its day, I will be blunt: a metallic thigh piece that a soldier wore. Sir Phillip Sydney refused to wear one because he thought they were ugly, cramped his dancing style, and were not necessary: he died from that mistake. In Cervantes’ novel the quichotte offers a bawdy allegorical joke: it stands as a phallic symbol which the old romancer cannot use. Today, the only people who wear a quichotte are American football players who are unlikely to know the origin of their equipment.

Rushdie confessed that he first thought of writing a non-fiction road trip work of journalism as a city man naively investigating the vagaries and viewpoints of rural life: a book about people quite different from himself. Then one of his sons declared he was too old to drive, and that he would drive for him. That slowed, or sobered, Rushdie up so much that he thought he might accomplish the task much faster by doing what he does best—using his imagination at his desk.

Since Cervantes’ magnus opus lives in two parts, the second part being far more amusing and intellectually intricate, Rushdie decided to write two parts at once in the same narrative–this postmodern thing that has it roots in Cervantes: Rushdie’s own autobiography (partially fictionalized?) as a parallel contiguous narrative. While the novel remains surprisingly accessible, it speeds down the freeway of twentieth century pop culture of both India and the United States, old and new worlds, connecting in rather miraculous ways. Anyway, one is left wondering who is real Quichotte: the fictional mirage, or the encyclopedia author who dreams and writes fiction.

Quichotte has been instantly nominated for the Booker Prize in England and will most likely put Rushdie in the running for the Nobel Prize. Joe Donahue is an adept interviewer who is continually on the road interviewing nearly every important writer who has something substantial to say. The last time Rushdie visited Bard was in 2006, which was so long ago that only historians know this fact, and even they won’t know this, or any facts when they, or we, pass beyond the door to death. But before one arrives at such dour observations, this perambulating novel of textured culture offers a carnival of fleeting sideshow amusements in this New World, where not much is new in the way of impossible dreams. Quichotte marvelously executes Ezra Pound’s maxim: “Make it New!”