by Kevin T McEneaney

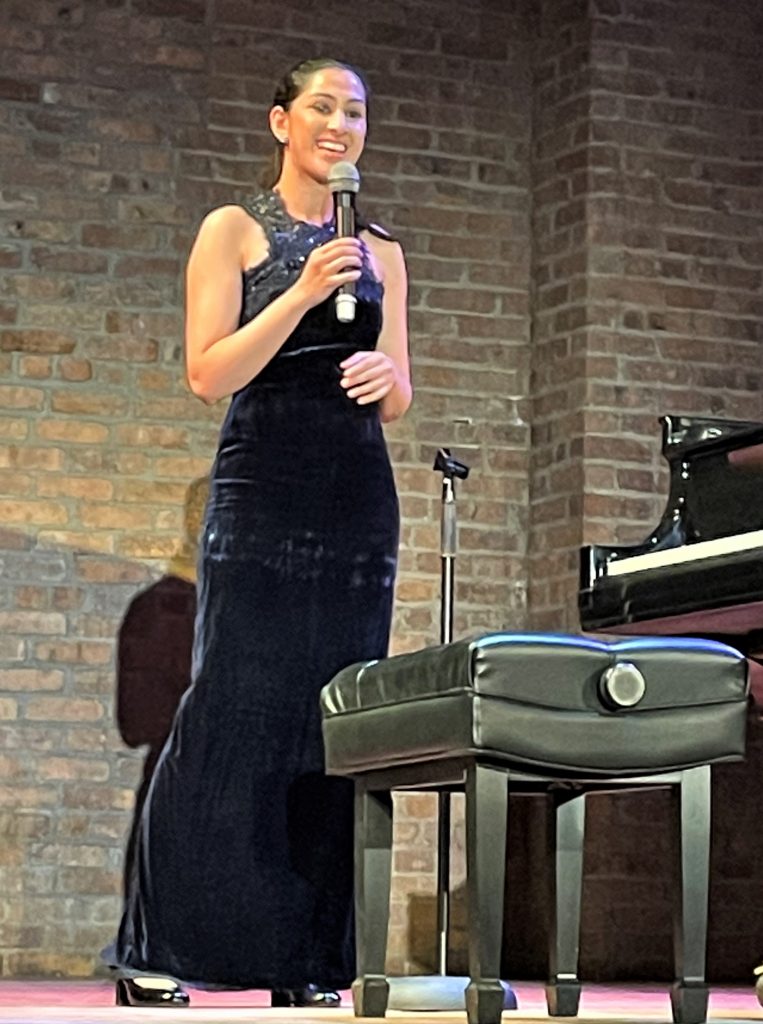

Champions of Salon Music offered a taste of mid-18th century salon music from Berlin, played by Mishka Rushdie Momen from England. Momen was the chosen nominee in the field of classical music from the Times Arts critics for the Breakthrough Award in 2021. A student of Richard Goode and Andreás Schiff, Momen has recently played at the 92Y in Manhattan, in Antwerp, and other notable stages around the globe.

From the opening chords of Felix Mendelssohn’s Songs Without Words, Op. 62, No. 5, I was awed by Momen’s clarity and dexterity, and the impressive force of her immaculate fingering. This breathless piece (published in 1844 in duet format) on the theme of Venetian boat singers, in A minor, captures the novel jollity of a boat ride through the canals of Venice with mimicking echoes of exuberant gondolier songs in the sway of a narrow boat. It is thought Felix may have played a version of this piece for Queen Victoria at Buckingham Place in 1842, during the second year of her marriage to King Albert. Felix had visited Venice in October 1830. There he was smitten by the epic paintings of Titian, which spurred him to compose. This exuberant recollection of liquid transport at Momen’s flowing digits made me feel like I was delivered to a holiday away from the tribulations of life and plunged into an alter-world of music that still rings in my mind hours after the concert.

Mendelssohn’s Variations sérieuses, Op. 54 (1841) presents a theme in D minor with 17 variations written when Felix had just become Kapellmeister to King Friedrich Wilhelm. Felix’s sister Fanny had joked in a letter that this position was “the highest human office next to the Privy Counselor and Pope.” Such narrow, disciplined, and serious explorations of the keyboard were not what the king had expected for his social entertainment, and after a year Felix resigned: yet this masterpiece is still played today! Momen’s powerful and incisive interpretation made me think of Hamlet’s quip: “O God, I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space.” This narrow exploration of a theme led me to think that such focus brought about the perception of infinity.

Prelude and Fugue in F Major, BWV 880 (c. 1740), by J. S. Bach, presented two intertwined themes with different voices in the Prelude, the second being an ascending theme in rapid quarter notes, of which Momen was a grand master. The complicated interlacing of the two contrasting themes becomes hypnotizing. The power of every changing chord delivers a swerving thrust during the five period sections. The work then concludes with a furious fugue that delivers a tonal “answer” to the dramatic conflict. This novel, dazzling, enigmatic puzzle made me think of a legendary grand master chess game, or the complex, somewhat comic, psychological undercurrent subtleties of the “battle of the sexes.”

Piano Sonata in F Major, Op. 10, no. 2 (1798), by Beethoven, followed up on the theme of duality in that the sonata explores the possibilities of the first two notes played. Development depends not on an ascending motif, but on a simple three-note descending motif. While dark shadows appear in the Scherzo, there is an echo of Mozart’s optimistic lightness in the pianissimo Trio movement.

The audience had been treated to three successive compositions by great masters that explored musical themes of minimal limits, hinting that that which is minimal might contain nearly unbounded possibilities.

Three movements from Fanny Mendelssohn’s seasonal epic Das Jahr (1841) were performed: January, June, and the Postlude chorale. This unique maximalist cycle contains a wealth of poetic ambiance; it is not played enough. The broad springtime joy of June is redolent with joyful flowers, and here Mishka Rushdie Momen offered a feminist reply to the three narrowly constructed male masterpieces.

Prelude and Fugue in C Major BWV 846 (1772) is the first of the 48 preludes and fugues from The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I. It is a piece based upon broken chords, played as if Momen were emphasizing the communication gap between the sexes. Since Bach’s book is an advanced instruction manual, he offers solutions to what is broken and how musical difficulties can be solved. Credo, by Arvo Pärt, is a homage built around this work; the song “Don’t Cry for me Argentina” is based upon a tune from this piece; the Brit band Procol Harum recorded an arranged rock version of this work on its debut album, A Whiter Shade of Pale.

For the finale, Momen played Chopin’s Ballade No. 2 in A-flat Major, Op. 38 (1838). The ballade, a medieval rhyming narrative format perfected by François Villon, was revived by Romantic poets as a way of writing political poetry for a general folk audience, a form in which Lord Byron excelled. Chopin completed this ballade in Majorca when he was living happily with George Sand. Although the couple later parted ways, this period of their lives was the high point of their romance, and so this concert concludes with a snapshot of the possibility of sexual happiness. I once heard this work performed weakly with the refrain dully repeated. The trick here is to play the refrain with varying pianistic inflection instead of rote repetition—which is often the problem in long-term sexual relationships. Momen excelled here in stripping away the overly faux self-reflective Romantic excess that often destroys in performance the profound pianistic achievement of Chopin.

Mishka Rushdie Momen, daughter of novelist Salman Rushdie’s sister, took to noodling at the piano at the age of five. Then, within a week, she taught herself to read music, so her father placed her in a music school for gifted children. She has the gift of perfect pitch, which significantly less than one in ten thousand possesses.

My friend Pete from Verbank remarked he was amazed a performance of this quality would appear in Pine Plains. I responded that the generosity of Stephen Kaye made such wizardry possible.