by Kevin T McEneaney

The organizing theme of this concert was water under the baton of Conductor Tan Dun. The concert opened with “Vitava” (in German The Moldau), part 2 of Bedřich Smetana’s masterwork written when he was completely deaf, Má Vlast (My Country). This part charts the symbolic joining of two streams to create the mighty river that molds the Czech populous into a single country. Here the clarinet of Miles Wazni and the oboe of Kai O’Donnell delivered the voice of hope and dignity yet threatened by the deft percussion section in the depiction of a mighty castle as the symbol of potential repression. The glories of the meandering river bank-side with Spring flowers are depicted against the potential of violent destruction.

Rhapsody for Saxophone and Orchestra (1901-03) by Claude Debussy appeared as a posthumous work. Commissioned by Elise Hall, an amateur saxophonist born in Paris to wealthy American parents, Debussy dabbled on-and-off with it, completed it, yet never it took it seriously, regarding the sax as “that aquatic instrument.” The finished work sways with aquatic stirrings with attractive melodies in Monet-like ambiance with fabulous flute melodies, yet the piece never appears to arrive anywhere, despite some delicious mellow solos by Eric Zheng. At this time in Debussy’s life, he was working as a music critic for Gil Blas and composing very little. But this little commission seeded the idea for his next big project—La Mer, his masterpiece about water. Tan Dun then presented in his own arrangement “Clair de lune” for orchestra and piano with Bat-Erdene Batbileg clearly clinking melodic keys.

“The Swan” from the Carnival of the Animals by Camille Saint-Sans with featured cello of Alexander Levinson (as the swan) was performed in a new arrangement by Tan Dun that spotlight-fronted the featured cello. I was enchanted by this new arrangement as the cello swam over the undertow of the orchestra.

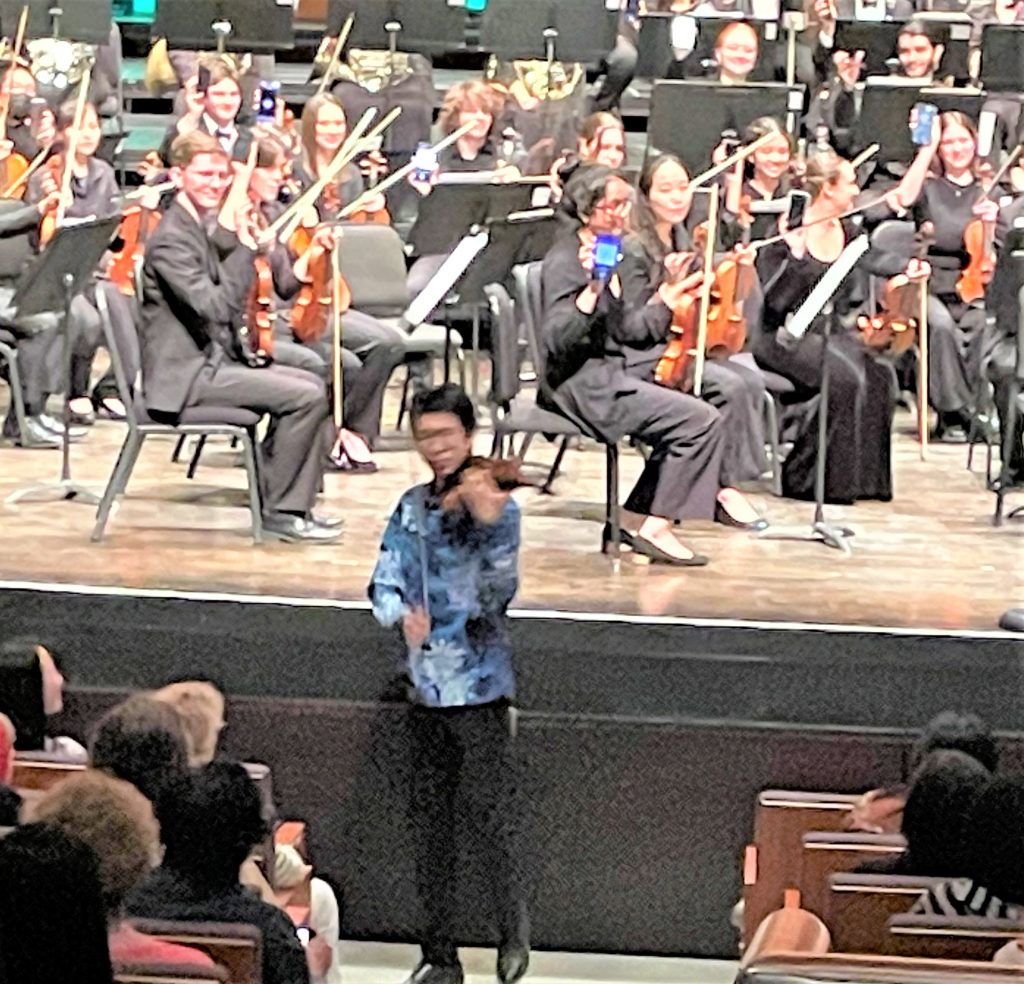

Ciocária (The Lark) by contemporary Romanian composer Grigoras Dinicu, grandson of Roma virtuoso Anghelus Dinicu who introduced this melody at the 1889 Paris World Exposition for which the Eiffel Tower was built, offered a memorable transition which made me recall Franz Joseph Haydn’s String Quartet in C major, Op. 33, no 3 where the song of a lark appears. The lead violinist swirled around the audience and mounted the stage as if to announce that there was also a circus-like ambiance to the contemporary crisis in American culture.

The Tokyo composer Toru Takemitsu was intensely influenced by Debussy’s La Mer and myths about the primitive dream-time origins of humanity which evolved into his masterpiece I Hear the Water Dreaming (1987). The flute of Francisco Verastegui floated out with great pleasure in this dreamy, languid composition that lingers in a timeless vector of hypnotic sound.

Four Sea Interludes, Op. 33a, from Benjamin Britten’s opera Peter Grimes (1945, these four movements were published the year before the opening of the opera as a preview) presents four aural tone poems on the sea: Dawn with a quiescent yet menacing, slow rise of the sun captures the anticipation of adventure with menacing brass harmonies as if a ship was an experiment in danger; by contrast Sunday Morning offers optimistic rhythmic tolling as a call to worship; Moonlight provides a throbbing ambiance of anxiety amid woodwind splashes and threatening percussive threats to safety as the boat is jostled to-and-fro on the ocean; climatic Storm fulfills the menaced foreshadowing, intimating disaster and shipwreck, which parallels the fate of the troubled anti-hero of the opera.

This is not a Turner-like Impressionistic painting, but the inner-emotional seascape of the character Peter Grimes’ tormented soul. Here Tan Dun brought out this interior landscape as if it were an echo of the current historic moment we are now living inside of.

The rather robust audience demanded encore bows.