Last Saturday evening at Bard’s Olin Hall the Isidore Quartet opened with one of Franz Joseph Haydn’s “Sun” quartets, Op. 20, no.2 in C Major (1772), one of the six quartets in the set that changed the trajectory of quartet music. The variety of texture and color has no precedent. The quartet opens without the first violin. It is as if the second violin, cello, and viola are three different people chatting and waiting for someone special to show up. The first violin, Adrian Steele, shows up with authority and begins to ask some probing questions, whereby a friendly conversation takes off between all four instruments with cordial, exciting, and heightened sonority.

The cello of Joshua McClendon appears to ask the most serious questions about what they, as a group, will do. Comic relief arrives in the third movement as the sprightly viola of Devin Moore dominates the conversation with amusement in the minuet, sowing myriad seeds of many possibilities for other instruments to follow. In the third movement the second violin, played by Phoenix Avalon, offers eloquent possibilities.

The delightful last movement, an intricate fugue that features a surprising inversion, intertwines all four instruments with agreement as volume and interplay discover an agreeable balance with finesse. This happy conclusion contains an infectious joy that effectively uplifts the whole audience. The sunny and affable joy that Haydn spills into the ears of the audience delivers a contagious effect. The composition is, in effect, a portrait of the 40-year-old genial composer who possesses the musical ability and temperament to charm anyone who will listen.

On a contrasting somber note, In Memory, String Quartet no. 2 (2002) by Joan Tower laments the loss of a mentor and close friend, Margaret Shafer, who guided and befriended the composer when she first arrived to teach at Bard College. This introductory lament is plangent and sensitive, then shifts into wider scope: the 911 event of the dual World Trade Center Towers in downtown New York City.

Personal lament is transformed into national, public lament with mingling fury and pathos. First, the event of the planes driving into each structure, the heroic attempt to rescue many people, and then the collapse of the buildings that were blown up from below offered a haunting horror. Both the first and second violins were riveting in their wailing while the cello groaned with sorrow as the viola appeared to ask the big question of why.

Joan Tower was there on stage to introduce the work alongside violist Devin Moore. The Tokyo String Quartet commissioned this extraordinary composition about death and loss and has performed this composition all around the globe, yet it was quite special to hear this memorable work in the locale where it was born. Some repetitive musical passages remain difficult to forget as the rising and falling sounds of the strings reverberate in one’s skull. (This work has also been arranged for string orchestra performance.)

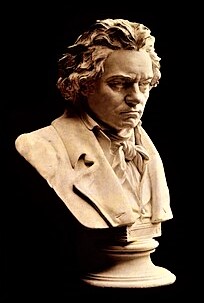

From the opening Allegro of Ludwig van Beethoven’s String Quartet in E-flat Major, Op. 127 (1822-24) we are asked to hear differently as the first violin leads three instruments with the effect of hearing an orchestra. This was the first quartet Beethoven wrote in the past ten years. The “threads’ of individual instruments appear to cross each other as if the instruments have multiple identities and various musical roles. It seems like there is no stability, yet there is no anarchy. Each instrument is a ghost of the other instruments as if they all lived in an invisible quantum dimension inside an atom which one cannot, of course, see or hear.

The feeling of song appears to guide the first movement and echoes within the following Adagio where the cello is dominant and the viola answers back with inversion as the first violin becomes a mocking comic. There is great tension, a technical striving between the instruments as they plunge spontaneously into the unknown.

And there is tremendous lyricism with deep emotions that produce in the listener a feeling of satisfactory mystery and even confusion tinged with ambivalence. To hear Beethoven’s latter quartets is to travel to an undefined location that is as satisfactory as it is disturbing and wondrous.

In the climatic finale, contrast is minimized, as if it were the beginning of a sonata, yet we are at the end of a complicated discussion and experience. The minimization of contrast lowers the sense of disagreements between jostling instruments and provides a sense of agreed resolution that offers a sense of individual and social resolution. There is an undefinable sense of catharsis.

The quartet played with the kind of seamless intensity that surpasses explanation and evokes transcendence. The audience demanded three bows and emanated that rare sense of levitation that puts joy in one’s stride no matter where you are going.

This extraordinary concert was part of a series sponsored by the Hudson Valley Chamber Music Circle.