by Kevin T McEneaney

The Balourdet Quartet, currently in residence at New England Conservatory, takes its name from Antoine Balourdet, chef extraordinaire at the Hotel St. Bernard and member of the Taos School of Music community; they originated from Rice University in Houston, first performing at Music Mountain three years ago as subs for The Julliard Quartet. String Quartet in E Minor, Op. 44 # 2 by Felix Mendelssohn. Number 1 and 2 announce Mendelssohn’s breakthrough to an original, intimate style, freeing himself from the influence of Beethoven; #2 preceded # 1. The passionate opening Allegro was likely written during his Spring honeymoon in the Black Forest with Cecile, which accounts for the brimming emotional ecstasy of the first movement performed with unified, robust éclat. Completed in 1837, it was slightly revived in 1839. Justin DeFilippis on first violin was blazing with impassioned enthusiasm. There is a melancholy urgency in the opening which dramatizes Felix’s unconsummated, courting love for Cecile. The sparkling Scherzo appears to record small pranks and jokes of the courting couple with impish rhythms. The Andante appears to chronicle the endearing progression of the courtship, while the agitated Presto appears to dramatize the likely acceptance of marriage with an explosive finale which records Cecile’s Yes. This impassioned work most likely influenced one of the most musical of novelists: James Joyce and his use of Yes in the Molly Bloom episode of Ulysses. This last movement was performed with such exquisitely delightful passion that the whole audience must have been thinking Yes, Yes, YES!

Strange Machines (String Quartet #4) by Karim Al-Zand (b. 1970) at Rice University is a clever, humorous piece inspired by the computer game Geometry Dash (2013 and its subsequent multiple versions), which offers musical sounds and images through algorithms (great for elementary school children!). Here we have a musical portrait of Leon Battista Alberti (1404-72), architect, poet, priest, historian, philosopher, linguist (he wrote the first Italian grammar), and the inventor of cryptography! Here the music careens about to depict the many angles of this legendary genius. Alberti was deeply influenced by Alhazen Ibn al-Haytham (d. c. 1041), an important Arab polymath. The work concludes with the sound of a wind-up toy whining downward. The music is the auditory version of a J. S. Bach-like jigsaw puzzle, employing fragments from J. S. Bach’s music. Goldberg Machine, the second movement, inspired by Bach’s 30 Goldberg Variations appropriates fragments from that work, re-arranging them (wittily) into something that sounds like an amusing Rube Goldberg contraption machine that ultimately collapses. Mannheim, the third movement, presents fragments from Bach’s Mannheim period and mixes them with fragments from the contemporary American musical group Mannheim Steamroller produced by pianist and composer Chip Davis. Mannheim Steamroller refers to a German waltz technique of a crescendo passage having a rising melodic line over an ostinato bass line, popularized by the Mannheim school of composition. The finale sounded like a steam pump collapsing. Each of the three comical movements of Strange Machines featured an odd and amusing doubling motif which will thematically connect with Rameau’s doubling motifs later in the concert. To introduce an exciting, substantial work of humor amid a program of serious works indicates exemplary panache.

Grosse Fuge, Op. 133 (1825) by Ludwig van Beethoven remains an unusual Beethoven quartet, one might say it is a Jacob’s robe of many colors—it is a puzzling mixture of motifs that magically coalesce into a whole, yet it is difficult to understand how this happens. The more one listens to the work, one’s pleasure in it grows. Fragments are seemingly haphazardly tossed about; one confronts confusion, yet one listens carefully, the finale appears as a great deliverance from confusion. On first violin Angela Bae excelled with fierce emotion while Benjamin Zannoni on viola stretched the range of his instrument to astonishing levels, and Russell Houston on cello delivered the lowest of low notes possible and it seemed like the three other players were standing on his shoulders. The unified dynamics of this performance rivaled the landmark recording by the famous Guarneri Quartet!

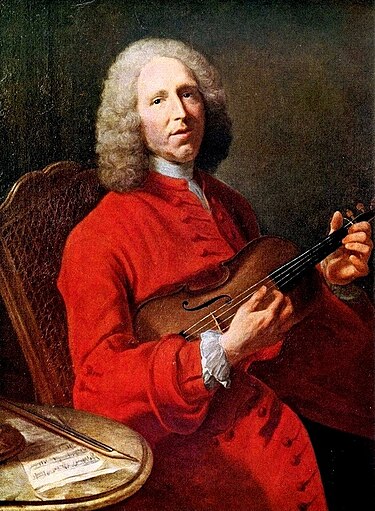

Gavotte and Six Doubles (1727) by Jean-Phillipe Rameau (first performance at Music Mountain), performed by Simone Dinnerstein, was written for harpsichord, yet is played on piano today with higher inflection. This youthful work by a contemporary of J. S. Bach offers a solo composition on the theme of dance, the year after J.S. Bach published his first works. (Some of Bach’s great works are meditations on dance.) Rameau was the first composer to aestheticize and spiritualize the theme of dance, as Bach later did. (Bach has a gavotte theme in Partita No. 3 in E Major for solo violin, BWV 1006). Here the word doubles indicate variations. The gavotte is a Celtic folk dance (popular in southeastern France and Brittany) performed with bagpipes and couples in circle-line dance formation with couples circulating while holding other couples’ hands. While the pacing of a gavotte can vary greatly, here there are seven dances played at a rapid rate rather too fast to dance to—a portrait of the week concluding with the vagrant playfulness of Saturday and the religious affirmation of spirituality on Sunday. A harpsichord intimates (with its higher register) a more spiritual realm (as does the organ). Both Rameau and Bach thought of themselves as men of the people (not aristocracy). Simone Dinnerstein captured the ardent everyday working labor of the week, plus the whimsical spontaneity of Saturday, and uplifting spirituality of Sunday as a day of rest.

(Jean-Jacques Rousseau had been commissioned to write all the music articles for the famous Encyclopedia edited by the autocrat-loving Diderot, yet Rousseau failed to meet deadlines. While Diderot was away on a trip, Rousseau had all the articles published. Rousseau praised Rameau over Lully and exalted Italian Renaissance composers. Diderot never forgave Rousseau—this was the first accurate account in French on the history of Renaissance music. Diderot later wrote an obscure novella satirizing Rousseau in Rameau’s Nephew.)

Keyboard Concerto in D Minor, BWV 1052 (1738) by J. S. Bach was completed during the two-year period when his pupil C.G. Gerlach took over his post at the Collegium in Leipzig, although some musicologists speculate that it was a revision of an earlier pre-Leipzig violin concerto. The concert began with clear lines of composition with the Mendelssohn, flirted with confusion, and now returned to clear compositional lines with the master composer who knew how to weld clear musical lines to wondrous effect employing Vivaldi’s trademark formula of fast/slow/fast. This work was likely meant for a large orchestra yet paring it down to a quintet worked quite well with Dinnerstein leading with fluid accuracy on piano with the Balourdet Quartet melding with such impressive tone and emotion that effectively implied that Bach was the Ur-father of the Classical music cornucopia which we now enjoy in such ever-relevant performances that we now enjoy at Music Mountain and other venues. The blended dynamics were ravishing and the audience rose demanding three raucous bows to complete the afternoon of an extraordinary program performed with such virtuosity!