by Kevin T McEneaney

Last weekend at St. James Place, Great Barrington, MA, and at Trinity Church, Lakeville, CT, Christine Gevert’s Crescendo choir, and small orchestra of seven instruments, presented the first known US production of Carisimmi’s oratorio Jephte (1648), which historians judge to be the first oratorio of substantial musical excellence. (The Roman Catholic Church had banned all performances of secular music during Lent.)

Giacomo Carisimmi (1605-1674), one of the first known composers of oratorio, the youngest of seven children born near Rome, had long been a choir singer, organist, and chapel master, becoming an ordained priest in 1637.

As in Greek tragedy, the performance begins with summary-background prologue. The Latin text is based upon chapter 11 of Judges in the Bible, which tells the story of the outlaw bandit Jepthe becoming the general of the Jewish army and making a vow that if he defeats the Ammonites (who demanded back some of their land which the Jews had previously conquered), Jepthe would become King of the Jews. Jephte makes a vow: if he is successful, he will sacrifice whoever steps first out of the door of his house upon his homecoming, if he returns victorious; his young virgin daughter steps out singing with timbrels. (I presume that in making the vow (supposedly to his version of God), he thought it would likely be one of his barking dogs.)

After granting two months of grace to live in the rustic mountains with her female virgin friends, Jepthe dutifully returns to her father to be sacrificed.

What a sorrowful story! And to hear its contemporary resonance with the women and children of Palestine today!

Psychologically speaking, this is a story to enforce the minor deprivations of Lent, which in its origin is derived from the Roman state religion that dedicated the month of February to penance for the five previous weeks of Saturnalia drinking and debauchery.

I was prepared to suffer both oratorio and mass (after intermission) yet was exceedingly enchanted with the plangent music that dramatized lament and lifted the staid repetitive language of the shortened liturgical mass to a higher level of sublime satisfaction. On the subject of war, they also tossed in one of the most popular medieval tunes: “The Armed Man” who destroys peaceful Christian civilization.

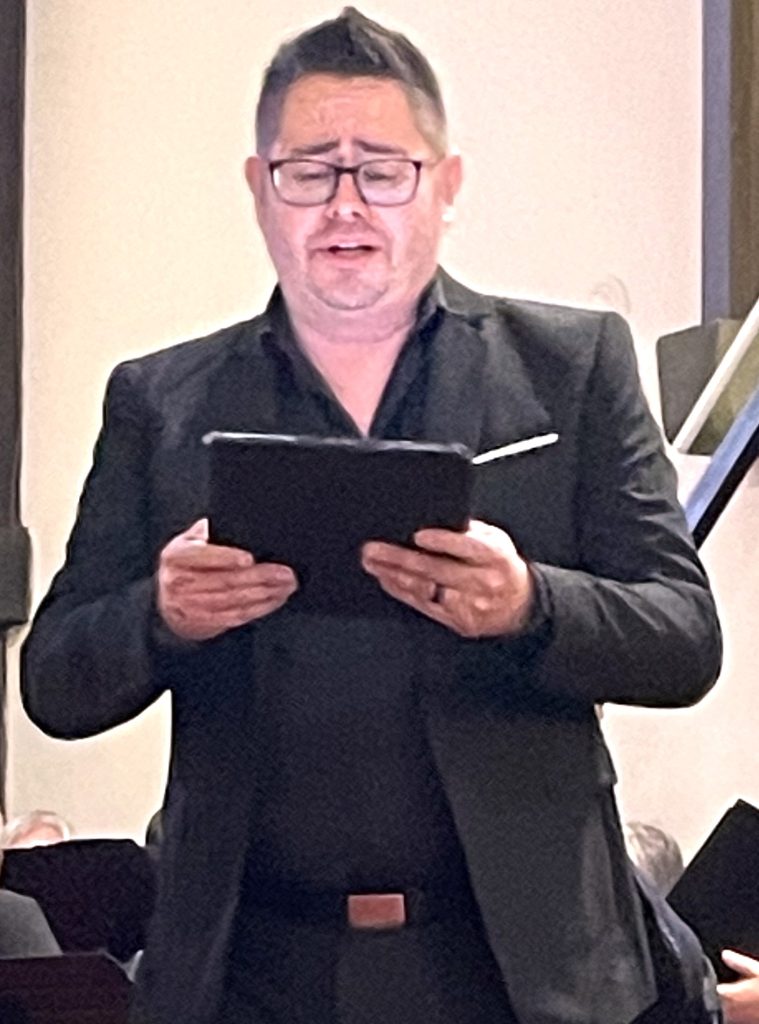

Christine Gevert conducted and played console organ with enthusiastic éclat amid the voices of a masterful choir script. The silvery voice of Soprano Christina Kay delivered piteous resignation with her fate. Tenor Pablo Bustos. Bass-baritone Douglas Williams was impressive with the lower somber tones of the tragedy. Soprano Jordan Rose Lee, who has been one of my favorites, sang with lively elegance.

In the female chorus altos Tuesday Rupp and Pat Barton sang quite well as they undertook to be emergency subs for a missing singer’s role in the historical narrative. In the men’s Chorus the voices of John Arthur-Miller and Gordon Gustafson stood out with clear diction and melodious projection.

Raechel Begley on recorder and dulcian delivered emotional grace in high notes and soft notes. Christa Patton had a near-monopoly on nuances. Hideki Yamaya on theorbo (the god-bow with long neck) contributed a climatic solo. Three viola da gamba players, Jane Hershey, Anne Legêne, and Erica Warnock provided affectionate mellow ambiance in the tragedy.

The comprehensive program for the event was meticulously researched by Chrstine Gevert.

P.S. George Frideric Handel with English libretto by Thomas Morell produced their own noted oratorio version of Jeptha in 1751. This was Handel’s last oratorio because of the loss of his eyesight. At the time, all staged works on Biblical themes were strictly banned, yet an exception was made for the 1752 production.