by Bill Schlesinger

A couple of years ago, being a weather-hobbyist, I added a particle sensor (Purple Air PA-II) to our rooftop weather station to measure the ambient concentration of particles that are less than 2.5 microns (um) in diameter. These particles, known as PM 2.5, which we can breathe deeply, cause adverse effects on health and increased human mortality. Lilieveld et al. (2015) estimates that about 3 million deaths per year worldwide can be attributed to PM 2.5 air pollution.

Much attention has been devoted to reducing air pollution from PM 2.5 particles. In North Carolina, implementation of the Clean Smokestacks Act, reduced PM 2.5 air pollutants, resulting in improved health care outcomes for much of the state. Similar air quality improvements have been seen across the United States.

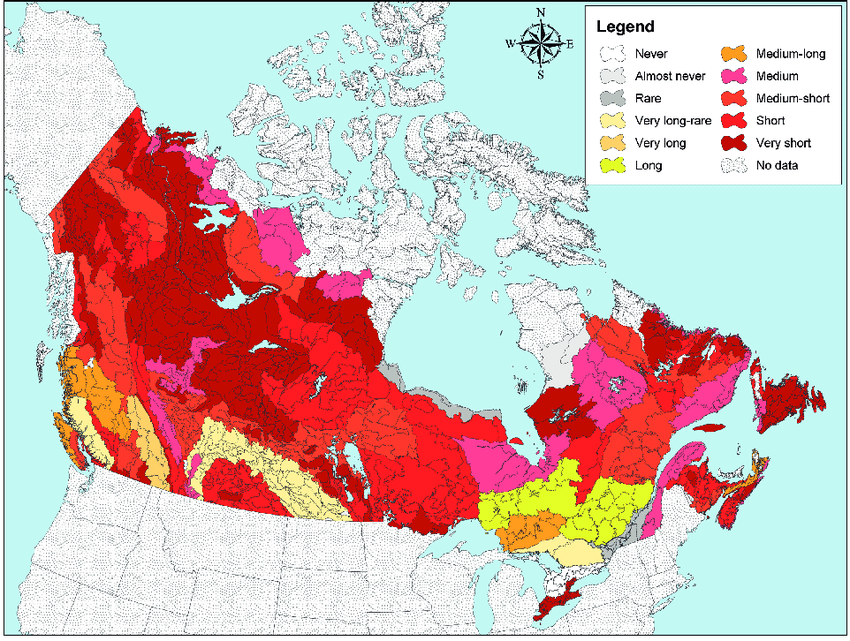

A couple of times this summer at our house in coastal Maine, the levels of PM 2.5 increased from their normal range of 1 to 20 ug/m3 to over 100 ug/m3. I thought we’d moved away from air pollution, but sure enough, the periods of this increase coincided with massive forest fires in Canada, which were a source of particulate pollution carried east to Maine.

Forest fires can produce enormous amounts of PM 2.5 locally, and recent fires in California resulted in dangerous levels of PM 2.5 for San Francisco and other cities. Globally, 77 million tons of fine particles are emitted from forest fires each year. Now, a new paper by Marshall Burke and his colleagues at Stanford University shows that this pollution can be carried long distances. They found that at least since 2016, wildfire smoke has reversed what had been a downward trend in PM 2.5 concentrations across the U.S., negating about 25% of the improvements in air quality seen from 2000 to 2022. In the past couple of years, some western states (WY, AZ, and NM) showed the highest levels of PM 2.5 ever recorded during periods associated with wildfires upwind.

These observations are important for several reasons. First, no matter where you live, your air quality is likely to be degraded when wildfires burn upwind. Second, hot dry conditions, associated with climate change are associated with higher levels of PM 2.5 from wildfires, which are likely to increase in the future. None of us will be immune from the effects of climate change on our health, even if we can’t see or smell the air pollution around us.

References:

Abatzoglou, J.T. and A.P. Williams. 2016. Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western U.S. forests. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113: 11700-11775.

Burke, M., and 7 others. 2023. The contribution of wildfire to PM2.5 trends in the USA. Nature 622: 761-766.

Lelieveld, J., J.S. Evans, M. Fnais, D. Giannadaki and A. Pozzer. 2015. The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale. Nature 525: 367-371.

Pope, C., M. Ezzati, and D.W. Dockery. 2009. Fine-particulate air pollution and life expectancy in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 360: 376-386.

Rhew, S.H., J. Kravchenko, and H. K. Lyerly. 2021. Exposure to low-dose ambient fine particulate matter PM2.5 and Alzheimer’s disease, non-Alzheimer’s dementia and Parkinson’s disease in North Carolina. PLOS One pone.0253253