by Kevin T McEneaney

This past weekend Bard College’s Sosnoff Theater resounded with The Orchestra Now in a distinctively American/Russian program. Despite being a major orchestral work, William L. Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony (1934, revised 1952) is rarely performed. The same might be said today of Dmitri Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony in C major, Op. 60 (nicknamed Leningrad), although it was once considered a monumental masterpiece (it is!).

Dawson’s project of combining African musical elements (especially rhythm) with traditional Western, classical music was in the tradition of W. E. B. Dubois’s concept of creating an African-American art of High Culture as opposed to the more aggressive “stand on our roots” perspective of Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston (Duke Ellington ambivalently straddled this political, aesthetic divide). The prolific art critic Alain Locke (Harvard educated, Howard College teacher) acclaimed Dawson while radicals leaned toward blues and hot jazz as a distinctive modality.

“The Bond of Africa,” the first movement, features a soaring French horn blues in which Ser Konvalin excelled, yet veers off into classical allusions to Dvorak, Bizet, and Smetana. After establishing such musical credentials, the second movement, “Hope in the Night,” explores the minor-blues landscape with deep emotional color, creating an earthy yet sophisticated dialectic that recalls the history of slavery. This movement is a masterpiece that needs more than one hearing.

The finale, “O, Le’ Me Shine, Shine like a Morning Star,” adumbrates the sprightly, optimistic American idiom that sparkles later in Leonard Bernstein and Howard Walker. This successful synthesis of classical and blues creates a new popular musical genre intended to integrate audiences in mutual appreciation and equality. While Negro Folk Symphony remains historically important, it also provides musical vitality that does not date; it firmly stands in the American musical canon as a work that should be performed in our traditional repertoire.

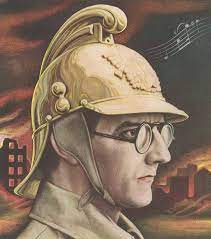

Dmitri Shostakovitch thrice failed the physical for the Red Army; he remained during the siege of Leningrad, and he joined the fire-fighting brigade of the Musical Conservatory, digging ditches amid bombings. Just after the Soviet government abandoned Leningrad, he followed and completed his Seventh Symphony, first premiered in March 1942; it was acclaimed as a powerful work of national patriotism in Russia while in Britain and the U.S.; it was perceived as an exciting defiance of Hitler. It became such a success that it annoyed vindictive Stalin who grew jealously furious when Shostakovitch appeared on the cover of Time magazine—from then on Dmitri had to be prepared for relocation in a gulag.

In the long first Allegretto (nearly half an hour), Concertmaster violist Zhen Li distinguished himself with his sensitive, high, lyrical tone (which was better than the recording I have). The depiction of rural, pastoral Russia delivers poignant affection, which dramatically turns to the disruption and horror of war in a fierce, threatening, discordant march (with Bolero-like repetitions), which develop incremental dynamic progression, concluding in a tragic requiem for those who lost their lives in the invasion. There is no mystery to this work, which remains accessible to anyone, yet at times it develops enigmatic ironies.

In the Moderato (poco allegretto) the oboe of Shawn Hutchison sang with clarity. This lively lyric intermezzo is the shortest movement. In the following Adagio strings and brass vie with strings echoing the opening movement, as if requesting a return to tranquility after the war while brass acclaims that that is not likely.

The concluding Allegro (non troppo) features protesting strings that clamor for an end to war while woodwinds announce continuance. The resulting frenzy of the violins arrive at colossal climax in C major, one of the most thrilling moments of any symphony. Here the strings of The Orchestra Now rose to this occasion with thrilling resonance.

There was a long, standing ovation in the partially filled auditorium.

There exists a muck of criticism, both for and against the Seventh Symphony. Like many extensive works, one may experience moments of longueur in one’s attention, yet this symphony retains a vital presence in both history as well as the present. In the end, Shostakovich’s incredibly high-quality output makes critique irrelevant; he stands as probably the greatest composer of the twentieth century.

Like Dawson, Shostakovich attempted to appeal both to popular audience as well as intelligentsia—an approach that usually annoys both political camps, and which often produces scorched-earth critique. Dawson abandoned symphonies and turned to prolific, academic critique in defense of his aesthetic values, while Shostakovich (like his close friend, satirist Mikhail Zoshchenko) soldiered on with inventing new shadowy ironies only accessible to intellectuals who might comprehend his bitter social critique, hoping that such people would bite their tongues and not speak of his spectral, eloquent critique until he died.