by Kevin T McEneaney

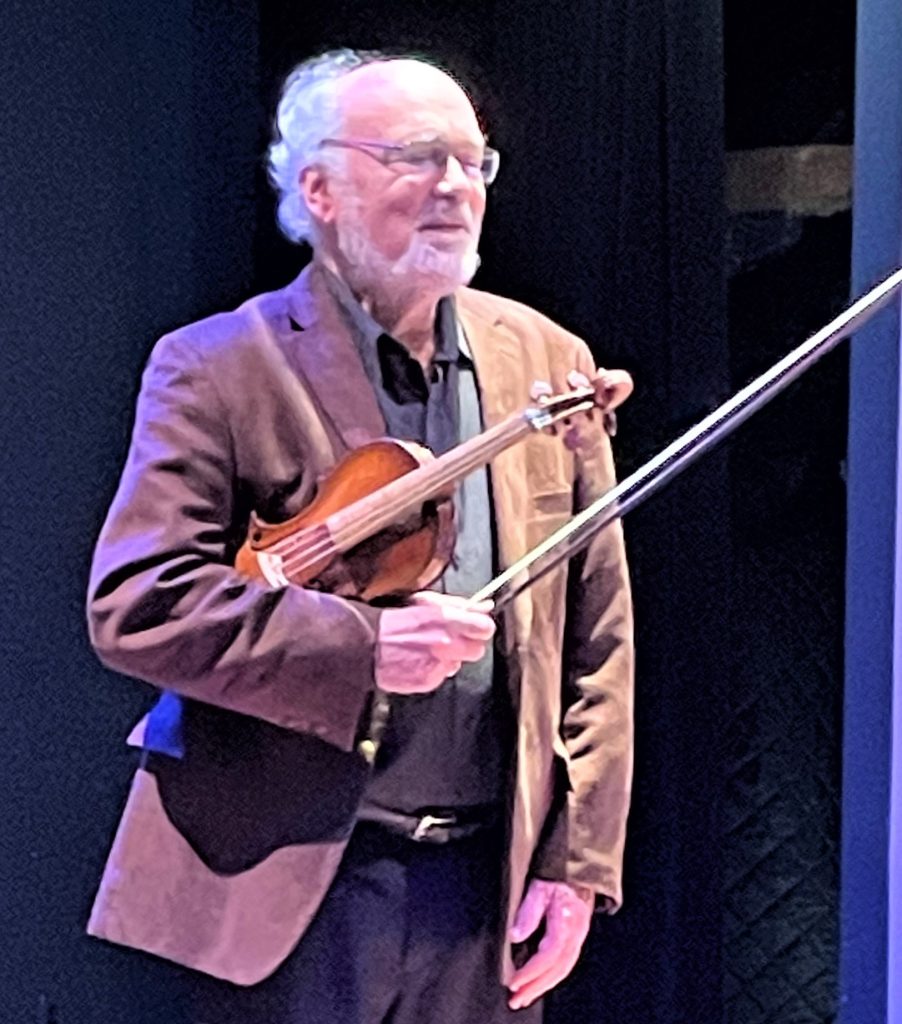

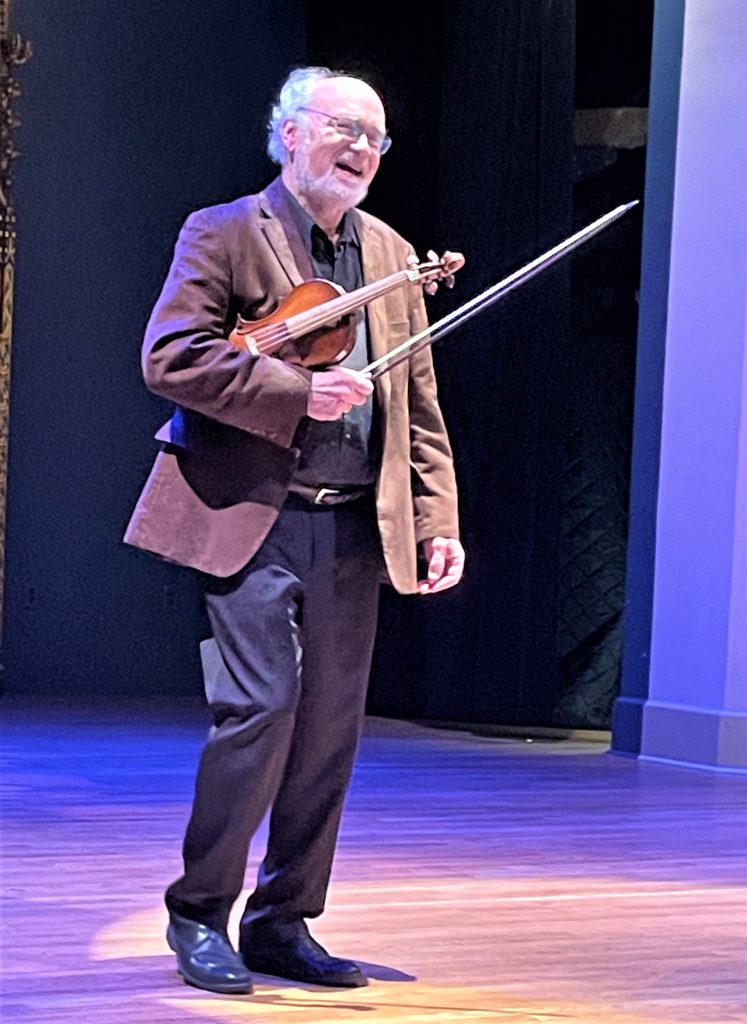

On Saturday evening at St. James Place in Great Barrington, Daniel Stepner of Aston Magna performed J.S. Bach’s three violin solo Partitas on baroque violin to an enthusiastic audience. These partitas were not published until 1802. David Ferdinand, Felix Mendelssohn’s favorite violinist, employed them as pedagogical tools, yet it was the Hungarian violinist Joseph Joachim who brought the work to the concert hall where it has become an icon for noted violinists.

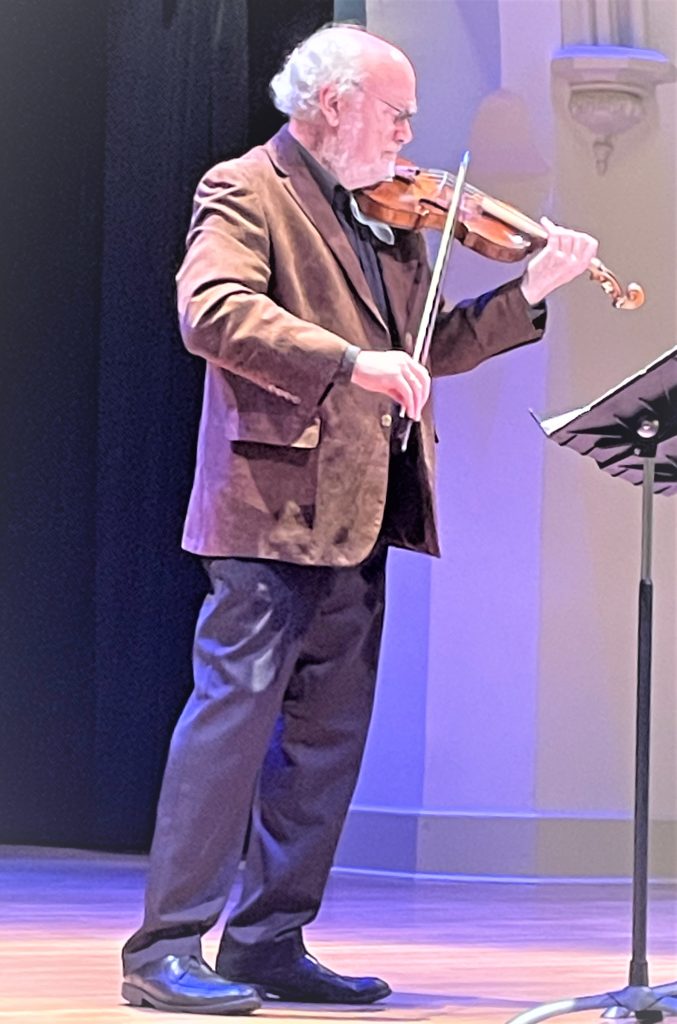

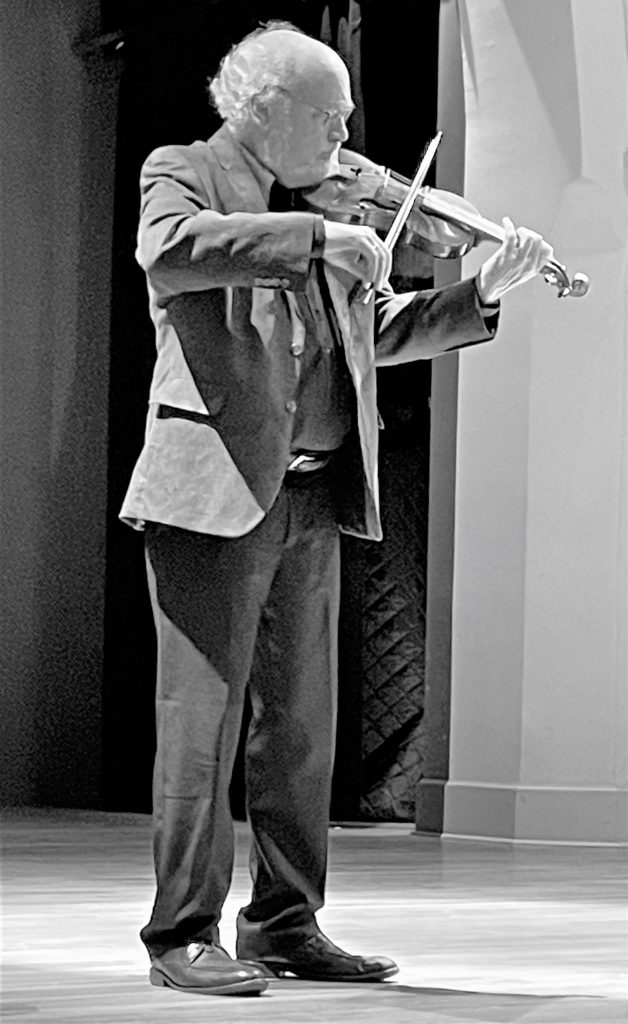

Stepner opened with Part III in E Major which features a long Prelude that functions as an invitation to a sequence of five dance movements. The Loure is a Norman (Viking) adaptation of the Celtic jig with a lilting dotted rhythm, the emphasis usually being on the first note with a moderate tempo. This movement was rather short as Bach appears to dismiss the dance as too simple for serious consideration. Gavotte en Rondeau is an outdoor Celtic dance from southeastern France near the Alps; this is a folk circle dance for couples that involves kissing, but French priests successfully removed the kissing. Bach appears to find the rhythm more charming, as Stepner indicated on his violin. Two contrasting minuet motifs followed. Minuet means short steps, a more polite, modest social form of dancing suitable for town meeting halls, estates, or courts. The shadowy contrasting second minuet appears to imply that the dance can be more intimate if the dancers wish it to be so, and so the shadowy version is preferred and arrives with some surprise and satisfaction; here Stepner delivered the hidden question with wistful intimacy. The Bourree, like the gavotte, is in double time yet it is a courtly dance that demands dancing and turning on toes (the predecessor of ballet). Here Stepner possessed a more eloquent yet subdued tone. The finale was the Gigue, a favorite of Bach, most likely because of its energetic drive which allows dancers to improvise their steps, dispensing that sense of freedom that Bach so admired and enjoyed: formality and convention becomes flexible and music more generously allows individual freedom, an aspect that Stepner communicated with his mischievous sense of joy in musical improvisation. This was a musical essay about dance stamped with Bach’s opinion.

Partita I in B Minor followed. Here were four dances played double: first the conventional manner of playing the dance, then followed by a shadow version with the shadow version being a lesson on how the conventionality of the dance may be enlivened. Here the opening Allemande is pleasant and its double rather more exciting. The Courrente, a court dance, has fast set steps that seem to run nowhere in 3/2 time; its shadowy double offers a satire, as if Bach reports that nothing of musical note can be done with this formal disaster popular in courts. Stepner adeptly identified the weakness of the genre. The finale was Tempo di Borea, an Italian gigue version with the tempo of a Borree, which offers a livelier social dance with the shadow double providing creative variations that infuse a sense of musical magic and satisfactory wonder, the moral being that gigue flexibility can improve the bourrée dance rhythm with joyous excitement—as delivered with robust fascination by Daniel Stepner!

After Intermission Stepner performed Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue in G Minor, BWV 903, arranged by D.S. Some commentators believe Bach composed this work to be played at the burial of Maria Barbara Bach, the first wife of J.S. Here, stunning free-floating arpeggios invoke the assumption of a body into heaven after fierce lament of wild dissonance, false cadences for what is not present, and harmonic ambiguities, which were later whimsically labeled as the difficult “Devil’s Mill.” Stepner outdid himself and I thought this to be a fabulous crescendo!

Partita II in D Minor followed. Once again, the subject is dance music: Allemanda, Corrente, Sarabanda, Giga, and Ciaccona. A plaintive four-bar phrase twists and turns on a roller coaster through both major and minor modes. Among violinists, this work is referred to as the chaconne. There is an infinitesimal gradual increase of rhythms in this work as if one begins going up a skyscraper in an elevator whose speed smoothly and nearly noticeably increases until the elevator blows through the roof of the building, and one is left jettisoned into free-floating polyphonic imagination. I think the reason this Partita was placed last was two-fold: it remains the masterwork that all violinists wish to climb (this most famous mountain), and secondly, it here functions as a memorial tribute to the greatest musical genius. While there is a wide range of interpretations about the performance of this work, Stepner’s version was strictly grounded in period interpretation.

The audience jumped to their feet with great applause and excitement, demanding three bows.

Next Saturday at St. James Place Aston Magna will present Side-By-Side: Schubert, Chopin, and Three Pianos, plus CPE Bach and Beethoven with David Hyun-su Kim, Guest Curator ion Piano at 6 pm.