By Kevin T McEneaney

The concert opened with Symphony No. 8 in B Minor “Unfinished,” D. 759 by Franz Schubert (1797-1828) under the baton of Dr. Leon Botstein. Schubert began the work in October 1822 but put the work aside at the end of the year with about half of the composition fully scored. Since it became a posthumous work, first performed on December 17, 1865, questions linger: would he have scored the remainder in the same way, or would he have made further revisions? Yet those questions cannot be answered. Concert halls have it and can perform this magnificent work if they wish.

Principal cellist Sarah Martin and the cellos as well as the basses under Athena Allen and her crew delivered an impressive opening in a movement dizzy with contrasts and containing sudden outbursts with deep pathos. Harmonic innovation dominates symmetry as an innovative Romantic modality leads to brash thematic juxtapositions burbling with volcanic, Manichean resonance. Classical balance has vanished with abrupt cadence from horns dismissing thrumming strings. In the recapitulation of the opening theme, the oboe of Alex Norrenburns poses a question, and the clarinet of Mohammed AbdNikfarjam replies. We feel that we have entered a mysterious Otherworld. There is a sense of immanent urgency in the harmonies.

In the Andante tonality becomes unpredictable, apocalyptic. Classicism has earned a period. We are on the edge of a new world. Classism is a negative, Romanticism is a positive. Was there to be a third movement?

If this work had been performed during Schubert’s lifetime, he would have been attacked, derided, and ridiculed. Today we appreciate it as a stunning Romantic masterpiece as we sit on the edge of our seats.

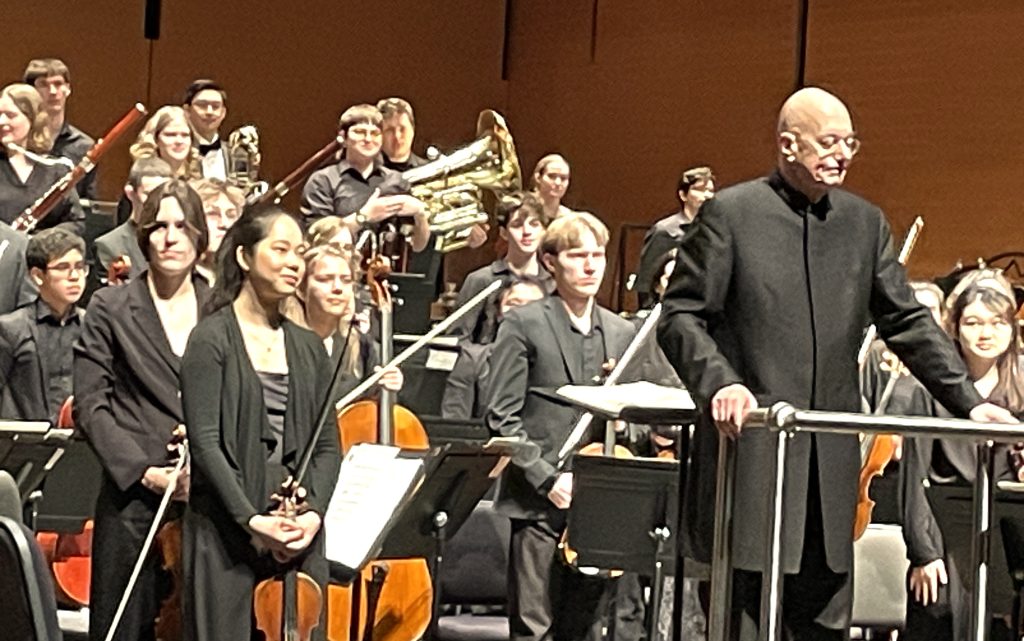

Psalm 42, Op. 42 (As the Heart Cries Out, 1838) by Felix Mendelssohn featured the Bard Chamber Singers performing in German, directed by James Bagwell with precise finesse. This ethereal masterpiece, bracketed between two secular works, offered an ambient religious aura shimmering with vocal ecstasy. The choir bracketed the secular orchestra on stage as if to state that great music lives on the perilous edge of life where religion becomes more sacred and forceful. Soloists sang with clear diction and deep emotion.

Symphony No. 10 in E Minor, Op. 93 (1953) by Dmitri Shostakovich remains a monumental work with controversies surrounding what the symphony is about. During World War II the public performance of Dimitri’s works was banned by Stalin who died while Dmitri was writing the symphony.

The opening slow movement in sonata form seems to describe daily difficulties before the war where the clarinet of Miles Wazni and the flute of Christian Midy enjoy leading two different melodies, the clarinet being metropolitan and the flute rural. Some suggest that it may be an allusion to a previous composition, Monologues on Verses by Pushkin (the second movement).

The second movement offers a short, peculiar scherzo which some think dramatizes the death of Stalin. Here the oboe of Kai O’Donnell excelled.

The succeeding Allegro movement puts one upright in your seat: arresting, fearful, piercing sounds of the war, and endless death. Here the clarinet may be ironic. Or this movement may be a description of Dmitri’s anger at being banned for so long. Or it may have been a way of competing with the shocking elements of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. Dmitri’s work often inhabits a slippery world that is objective, subjective, or both (and sometimes with ambiguous irony for his protection). Yes, this movement is shockingly great and meant to be heard more than once!

Some critics acclaim this symphony as Dmitri’s greatest symphony, yet one must consider No. 1. No. 5, No. 7, and No. 14! Dmitri may be the greatest composer of the twentieth century. He can be the most enigmatic.

This contrasting technique of Shostakovich appears to parallel the vivid contrasts in Schubert’s Symphony No. 8 which sounded like it employed a Manichean perspective. Perhaps that is why Conductor Leon Botstein paired these symphonies to showcase such vivid parallel progressions.

It is commonly thought that the following Allegretto contains keys that spell out Dmitri’s name in German and the name of a young 24-year-old piano student of his with whom he corresponded as his wife was dying. Dmitri said that this movement occurred to him in a dream; it appears to be influenced by Gustav Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth). Here the horns were masterfully played, and percussion by Nora Regina Graf was superb. This movement is either an exalted romantic sublimation or an articulation that joy and happiness will return to the city and rural landscape with an end to the atrocious war. Or perhaps both, as a gracious oboe solo by Kai O’Donnell admits that the desired affair will not happen. Or a concluding observation on our mortality.

Under Stalin music had to be politically correct; personal statement and autobiography was taboo. A personal statement could put one in a slave work camp. Combating an avalanche of inane critics and denunciations, composer Aram Khachaturian dared to praise the originality of this work, declaring this symphony as “an optimistic tragedy, infused with a firm belief in the victory of bright, life-affirming forces.”

This symphony, which took two years to write, is one the greatest and most brilliant musical riddles…

And so, it was no wonder that this concert, despite the cold night, was sold out!