by Kevin T McEneaney

Terrence Wilson, an acclaimed pianist of great vigor and sound who has toured the globe’s great musical halls, made his debut at The Stissing Center last Sunday. Wilson performs by memory without a score. He opened with a new, unrecorded composition by Lowell Liebermann, one of America’s sterling composers who has written over one hundred fifty works. Wilson opened with Liebermann’s Moment Musical Op. 144, which was commissioned by the Hilton Head Symphony Orchestra and Hilton Head International Piano Competition. This piano composition opened with an energetic, wandering meditation that brimmed with contrast, yet remained serious and elegant. The first movement appeared to be a lively recollection of childhood with a golden glow that documented his falling in love with the piano in his youth.

The dramatic and deeply emotional second movement described the artist’s growth at the keyboard from burgeoning pianist to his first major concert appearance at the age of sixteen on the stage of Carnegie Hall and subsequent appearances around the globe. Both movements were strikingly memorable: the playfully erratic youthful first movement and the thrilling, mature roller-coaster of the climactic second movement. This magnificent, introspective work was likely inspired by Moments musicaux Op.16 (1896) by Sergei Rachmaninoff. I was thunderstruck by the performance and wished to hear it again, yet there is, as yet, no recording of the work.

Wilson then performed Études-Tableaux, Op. 39 (1917) by Sergei Rachmaninoff, which is rarely performed due to its intense difficulty. In nine movements, the score splashes keyboard colors and acrobatic technique at a speeding pace. This abstract masterpiece of immense virtuosity explores both the limits of the piano and the supple dexterity of the performer.

The first movement, both expressive and technical, delivers a mood of exaltation based upon the theme of the ocean, where the keyboard swells with arpeggios. In the second movement, the sea is calmer with the flutter of seagulls visiting the ship. The unusual third movement delves into the conundrum of how the weaker fingers of the hand cope with sudden swells. Wilson managed to sound as if the weaker fingers were as strong as the first two fingers! The fourth movement offers a focus on repeated notes and how many such notes can be successfully repeated, or not. The fifth movement examines contrasting octaves.

The sixth is a study in repeated notes and sensational jumps. The seventh is a meditation on a funeral march with solemn chords and ringing bells. Here, Wilson was simply magnificent with the resounding bell effects. The eighth is an exploration of double notes. The concluding ninth delivers a triumphant resolution to the problem of octaves, swelling jumps, and notes that can be successfully repeated. The arc of the work is from unexpected excitement to an exploration of what is difficult or nearly impossible to a finale that appears to accomplish what was hitherto thought to be impossible. Wilson proved with vigor that playing this composition was possible for a talented pianist. (Rachmaninoff enjoyed exceptionally large hands; it was many years before other accomplished pianists could play this monstrously difficult work.)

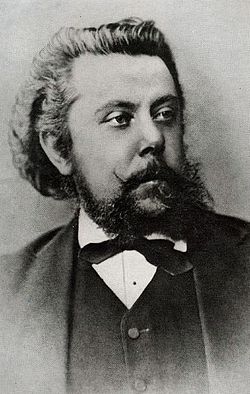

Pictures at an Exhibition (1874) by Modest Mussorgsky was stimulated by a gallery of drawings and paintings shown in Moscow, which favored the magical, grotesque, heroic, exotic, and grand. At this time, Modest was haunted by the unexpected death of the painter, traveler, and architect Victor Hartman, one of Modest’s closest friends. This piano work was not published until 1886, five years after the death of Modest.)

The opening recounts the footsteps of Modest entering the gallery. Each of the ten movements recounts a particular drawing or painting. The first is of a hobbling bow-legged gnome, the second a troubadour singing at the gate of an old castle. The third is a depiction of children playing and squabbling in the Parisian Tuileries Park. (From a lost painting by Hartman.) The fourth is a Polish cart drawn by oxen. (Probably another lost Hartman painting.) The fifth was a sketch of ballet costumes for young children in shell costumes.

The sixth was a Hartman painting of two men arguing about a cow in Limoges, France. The seventh comprised two portraits, one of a rich Jew and one of a poor Jew, based upon two separate paintings that Hartman had gifted Modest. The eighth offers a self-portrait of Hartman and a tour guide in the Roman catacombs, the tour guide being a portrait of Musorgsky. The ninth is a painting of a Russian clock with the painted motif of a Baba-Yaga sitting on a mound of eggs. The tenth is the great Bogatyr Gates in Kiev, which offers a dramatic, resounding promenade conclusion as everyone in the audience breathed an explosive WOW!

The standing audience demanded two bows. I felt like staying put rather than leaving. The concluding bells at the gate are still ringing in my head!

This was a fabulous concert to remember for a lifetime!