On a Dark Night with Enough Wind by Lilla Pennant. Published by Y Lolfa. 160 pages. Reviewed by Antonia Shoumatoff.

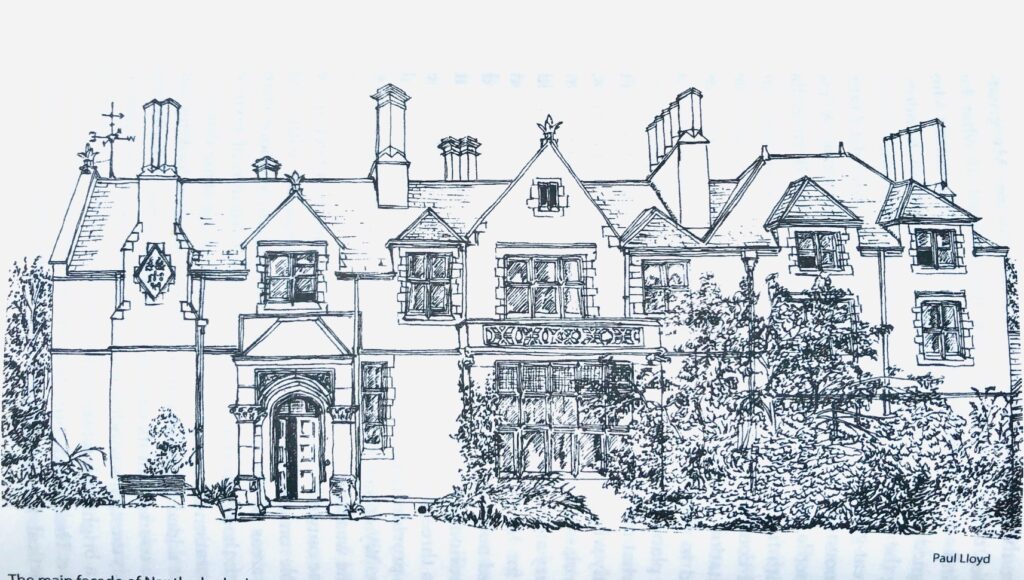

Lilla Pennant grew up in an English-style manor house with forty rooms called Nantlys in North East Wales, a region called Tremerchion. She is English with Welsh forebears. Her stories cover both the upper crust and the underbelly of an relatively unknown region, formerly known as Lleweni, home to around 1,500 people. Her family’s manor house was known simply as “The Hall” by Welsh locals and was designed by the prolific Victorian architect Thomas Wyatt, who designed many of the most impressive country houses and churches in the 1800’s. She became intrigued by the secret histories of those who lived in the small stone cottages that dotted hillsides around her family’s home.

Over a long period of time, starting in the 1970’s, she gathered the histories of the families in the area by gaining their trust and friendship. The stone cottage dwellers, many of whom had grown up with no telephone, sanitation, or even indoor running water, were astounded that a “Daughter of the Hall” would be so interested in them. She managed to achieve this by acquiring and restoring a stone cottage herself, climbing on the roof to fix holes in the slate and tending to the garden. She was able to gain their respect by becoming one of them and started self-identifying as Welsh, even though she had lived in London as a journalist for many years.

The hill dwellers subsisted by trading and bartering, as well as by an ingenious system of illegally trapping rabbits at night in long nets, a secret that was fiercely guarded in the area. She interviewed many of the last residents who remembered this practice and gathered their stories and histories. Her place-based book is a fascinating and valuable document of the region called Sodom, a region that has no written records. As she delved into each person’s story, the locality “changed from being a place of puzzling shadows to a bustling community with tales more curious than I could ever have guessed.”

“Hellaw!” exclaimed Trevor Jones (with the Welsh emphasis on the second syllable), when she first approached him near his sheep fields in Pant Glas, an area owned by her family. At first when he realized she was the daughter of his landlord, “he seemed bemused to see one of the Pennants [of the Hall] working hard like an inhabitant of Sodom.”

Then slowly he propped up a foot on the stone wall and started recounting the old stories, reciting the saga of the area with the prowess of a “performer whose vocation was to tell stories.”

She found out that he had ‘learnt about the herbs,” and made herb beer. Bunches of desiccated herbs hung from the rafters of nearly every kitchen in those days, and were used not just as teas and tonics but to treat every family and animal ailment—being turned into ointments and soap with animal fat.

After Ms. Pennant inherited the family mansion, the younger generation could not afford to keep it up with its thirty-four hearths and rooms “so distant that no one visited them for weeks.” She and her sister had to empty out the home of troves of obscure books, chests of costume jewelry, candelabra, photos, sealing wax and other “scarcely disturbed remnants of Victorian England” before they sold it.

Wanting to save a least one of the family houses, she persuaded her father to give her Henblas Hall a smaller stone manor house. She then felt that she “crossed over” from being just English to being accepted as “just another eccentric who lived in Sodom.” The strange and sometimes reclusive hill dwellers slowly opened up to her, only finally trusting her enough to tell of the how the rabbits were caught at night.

“You can’t do anything on a night with a moon. The keepers can see you a quarter of a mile off in the moonlight, and you need wind. You need a dark night with enough wind. You have to go around them [the rabbits], not making any noise and keeping the wind always coming from behind them,” just at the time when the rabbits are out eating. The rabbits have wonderful noses and if the wind blows towards them, they will smell you and bolt. “If the wind is coming towards you and is strong, it’ll carry the sound of your footsteps away.”

Thus the poachers in Sodom became better at catching rabbits than anyone else in the vicinity, using 400-foot long netting. They made enough money in one night to live on for a month. Of course, they occasionally trapped a badger or two as well, so those creatures had to be disentangled.

The ones who participated in the dark night rabbit netting were a strange lot: “It was the recluses and the men who loved company alike. The kind and the cruel, the friendly and the hostile, the unemployed and the employed,” explained Pennant. The rabbits were hauled in sacks and underneath baskets in secret compartments by women taking their onions, carrots and potatoes to market. They were traded to dealers from as far away as Liverpool. The rabbits garnered four shillings a pair as far back as 1919.

Rabbits were eaten for breakfast, lunch, and dinner—wrapped in bacon and fried, roasted, and boiled. Some of the women attributed the unsual height of their children to eating rabbit!

But the wall of silence around the practice was impenetrable. And no one got caught or went to prison. Unfortunately, the situation did not end up well. A disease, fatal to rabbits, believed to have come from Australia, spread through the district causing mass rabbit die-off. The disease was called myxomatosis. Every warren had rabbits dying in the most painful way. They lost their fear of humans and appeared in the fields in the most pitiful way, as if asking for help. Farmers shot and buried them to prevent their children from seeing the awful suffering of the creatures.

The rabbits all disappeared. And so did the hill dwellers. “We stayed for another two or three years, but we could not afford to live,” said Trevor, “Why did everyone leave after the myoxi? They had nothing to eat. Everyone who had been living off the rabbits left and suddenly the mountains were very quiet.”

Pennant has done the yeoman’s job of telling a poignant story and in the process preserving critical history. The book is illustrated with charming line drawings by Paul Lloyd and Myriel Edge.