by Kevin T McEneaney

Arianna String Quartet brought a smoothly textured program of intense energy to Gordon Hall last Sunday on a day bathed in mild sunshine. To wet the appetite of subsequent audiences who will be treated to a complete sequence of Haydn’s “Sun” quartets by a variety of string ensembles, they played Haydn’s Op 54, #1 (1788).

My speculation on the meaning of this rather extroverted string quartet resides in the court: the first violin, played with authority and vigor by John McGrosso, represents the enthusiastic King who is planning a public event; the second supporting violin, played with ariel ascent by Julia Sakharova, is the modest Queen making small suggestion about the event; the viola, played with acute sensitivity by Joanna Mendoza, represents the Master of Ceremonies, who will oversee the event; the more somber and cautious cello, played with serious sonority by Kurt Baldwin represents the Treasurer who, at times, would prefer to cut some expenses as the planning builds enthusiasm. The King is exuberant with his plans, his excited fantasy growing unchecked in the opening “Allegro con brio.”

The following “Allegretto” depicts a second planning session that is less fanciful, more realistic, discussing sticky details. There is a more intimate, frank, even tender discussion about the event occurs, as the lead is passed back-and-forth, and around. The following “Menuetto Allegretto” depicts a rehearsal of the public event where the cello plays a stronger role in warning, correcting, and critiquing the performance of the rehearsal. The “Finale: Presto” is a high-spirited dramatization of the successful event—perhaps a banquet with music and dancing, the musicians themselves here playing at the peak of their talent and asserting the event to be a wonderful success. Perhaps you heard the quartet differently—I am merely reporting the pleasant fantasy I heard in the music.

Reena Esmail (b. 1983) is an Indian-American music composer of Indian and Western classical music with a doctorate in music from the Yale School of Music. She is composer-in-residence at the Los Angeles Master Chorale and Seattle Symphony. She spent a year in India investigating her Indian roots, absorbing Indian music. The result was her String Quartet, Ragamala (2013), which employs the structure of various tones and drones of Indian music in the format of a European quartet.

This piece opened with a great sense of joy and exploration: birth, then depicting the joys of childhood. I thought the second movement described the tensions and disappointments of early adulthood; the third movement depicting the satisfaction of mature adulthood despite its pitfalls, while the concluding movement delved into the problems of old age, the somber, concluding cello solo dramatizing the final moments of decline and death. The work offered an epic tale of the classic four ages of humankind, capturing the whole arc of life with intense emotion and plangent meditation. As a first-time listener I was enraptured by the process and depth of the composition which projected a range of complex emotion with minimalist notes —it is an unusual contemporary classic that, as they say, has legs. I was excited that the Arianna Quartet was bring something new to the traditional classic repertoire played at Music Mountain.

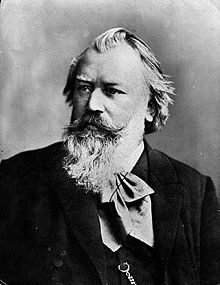

Pianist Ruth Gordon joined the Arianna String Quartet as Guest Artist for Quintet in F minor, Op. 34 (1864) by Johannes Brahms. Gordon teaches at Smith College. In 1997 The Boston Globe acclaimed Gordon “Musician of the Year.”

Quitting his choir post in June, 1864, Brahms spent the summer in Lichtenthal (today part of Baden-Baden) near where Clara Schumann vacationed with her children. Perhaps Brahms had two muses to inspire this quintet: Clara and the relaxing rural landscape away from the city. First composed as a piano quartet in 1862, this popular Sturm und Drang masterpiece (this was its forty-ninth performance at Music Mountain) underwent several complicated metamorphoses before arriving at satisfactory format.

Dominated by the interval of the minor second, which communicates great disturbance, this work may be a declaration of Brahms’ formidable, yet frustrated, attempt to woo Clara into a second marriage. As in Ragamala, small tones develop into dramatic landscapes with a surprising and sinuous unity (although in Ragamala there is self-less, deep spiritual meditation, rather than public affirmation of what is private).

This quintet with its Neapolitan inflection inhabits a fever-pitch of exclamation marks that run to a vanishing horizon! What is simple becomes complicated and what is complicated eventually appears as simplicity itself, due to the intense unity of the composition, which in the playing here on stage swelled to achieve that longed-for intoxicating unity. If the performers don’t have that mystic, magical co-ordination, then the attempt at ecstasy is for naught, and here the audience was thrilled to rapture, as if the audience was a single being, rising and applauding, demanding several bows from the exhausted performers.