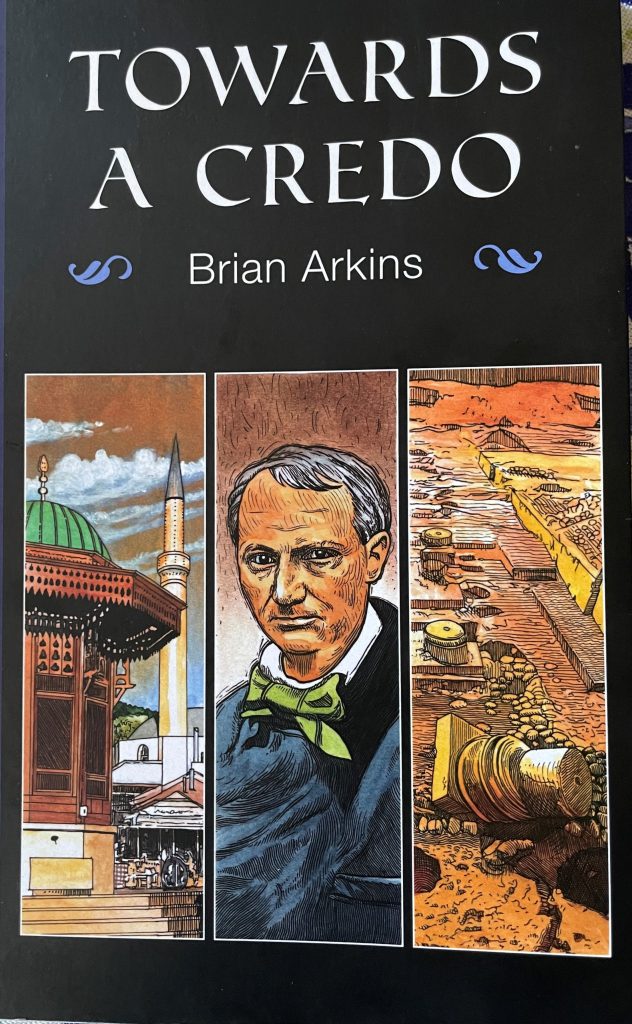

Towards a Credo. Brian Arkins. Little Gull Publishers. 36 pages. 2022.

Reviewed by Kevin T McEneaney

Brian Arkins is not only Ireland’s leading Greek and Latin scholar, he is also well-known for shedding light on Irish poetry, plays, and Anglo-Irish writers like James Joyce. After about thirty volumes of astute commentary, he wades into stream of Anglo-Irish poetry with original poems and some poems well-translated from the French—Baudelaire and Verlaine. The book’s title freights a demand for honesty and commitment in the arts. Baudelaire advised that we get drunk with wine or virtue, and which we prefer does not matter—the point is to be committed to honesty and work:

Poets must suffer for their love

and though they rant forever of desire and lust

rarely is woman a close-fitting glove,

never when the artist lives as he must.

Most of the volume (impressively designed, both cover and layout) is composed in idiomatic free verse, yet this pithy stanza dramatizes accurately the fate of a poet who must, necessarily, inhabit a peculiar Otherworld with limited connection to the conventions of ordinary life. Poetic vision arrives with a serious price tag that only the avidly committed can survive (or not, as the case may be).

Much of the discursive and observant poetry remains self-consciously literary. In that vein. I loved the humor of a list of unwritten books by famous authors: “What I believe in by William Shakespeare” or “The Mothers of Walt Whitman’s Six Children” and other witty lines.

By turns the poems are sardonic, lyrical, incisive, and entertaining. His translation of the recently discovered Sappho poem in the Bodleian Library is by far the most acute of current published translations, which concludes:

Then they say that rosy-armed Dawn, smitten with love,

once carried off Tithonus to the end of the world,

beautiful and young then, but in time grey old age

overtook him, who had an immortal wife.

Competing translations lack the elegant concision of the conclusion, which in its somber and arresting brevity resembles the geometric axioms of Euclid.

Other subjects: the often-ridiculous mythology of Christianity, the fierce blindness of doctrinal belief by atheists, the mad, cruel, perpetually useless illusions of war, and the difficulty of turning mere watery words into the enlightening wine that reveals truth, beauty, and the flawed fatal irony of the human condition.