by Kevin T McEneaney

The Sherman Ensemble at St. Andrews Church in Kent opened Friday evening with Franz Joseph Haydn’s Divertissement No. 2, Op. 100 for Flute, Violin and Cello (composed in the summer of 1784, the winter Haydn performed his first opera Armida for the Esterházy Court) with Susan Rotholz playing her steel flute with an unusual, new wooden mouthpiece made by a contemporary craftsman.

Accompanied by her husband Eliot Bailen on cello and Paul Woodiel on violin, they performed a lively, engaging, Minuet-like opening recalling court dance. The Allegro was followed by a meditative, serious Adagio as flute lead with solemn and eloquent gravity to remind the two suitors of the gravity of marriage commitment. The sunny, nearly comic, Allegro Finale brims with extroverted joy captured by Paul’s violin, while Eliot on cello offered what sounded like courtly, genial, robust wit replying to Paul’s rustic, improvistic fancy as Susan’s flute floated above like a fairy referee encouraging accompanists to aspire to her celestial charm. The humor of this work remains entrancing.

This difficult piece is rarely played because there is a famous recording of it by Jean-Pierre Rampal with Isaac Stern and Mstislav Rostropovich on CBS Masterworks (1983). And yes, this trio mounted a mighty challenge to that recording and it was live music reverberating in air with an audience of sophisticated, masked connoisseurs! Redolent with mid-summer romance, this musical idyll about courting appears to flatter some young noble lady at court, whose vivacious intellect would more likely incline her to choose the more sober and witty cello over the lusty violin. What a delightful opening!

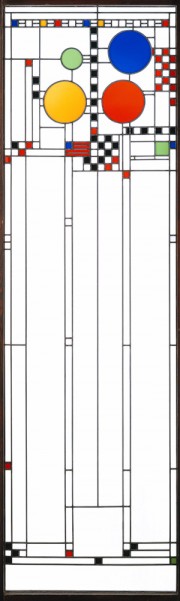

Andrew Norman’s Light Screens for flute, violin, cello, and piano (2002) was inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright’s stained-glass window designs, which he termed “light screens.” These designs use simple shapes like the square and the rhombus in repetitive patterns, and they often feature a lively dynamic of asymmetry between areas of intense geometric activity and expanses of largely empty space—this was characteristic of the music with its vibrant tonal contrasts.

This piece became more widely known once it was taken up by the Cassatt Quartet who will perform this Sunday at Music Mountain. (It also made me aware that this work had immense influence on the contemporary work of Norwegian composer Ola Gjeilo who now lives and works in Manhattan.) This performance featured the same players as the Haydn quartet. The minimalist purity of Norman’s lines is both refreshing and exciting—a work worth more than one hearing!

Be Still and Know (2015) by Carlos Oliver Simon, Jr. (b 1986), currently Assistant Professor at Georgetown University (formerly of Morehouse College), is a much-lauded composer of jazz and classical music who now writes for leading American orchestras. This work became the soundtrack for an indie movie of that title (about four female childhood friends who come together for a reunion in a rural Tennessee cabin). With bold rhythmic changes and arresting chord changes, this slow meditative piece entrances the listener to commune with transcendence in their lives as it explores the question of purpose in life.

Originally a piano piece, this work was performed as a quartet with Margaret Kampmeier on piano lyrically leading Susan on flute, Eliot on cello, and Michael Roth sensitively playing violin. The serious and sober nature of this adept composition became a shadowy foil for the fireworks to come.

Piano Quintet, Op, 34 in F minor (1864) by Johannes Brahms remains one of the great jewels of the nineteenth century. First conceived as a string quartet, Brahms destroyed the work, then re-conceived it as a quintet with two pianos, yet finally settled on a quintet with one piano. Soft, mellow lyricism contrasts with robust bursts of intense ensemble explosions that nearly raise the hair on one’s head and force one’s eyelid to its upper reaches in wonder. This was the wondrous work that firmly established the career of Brahms.

What makes this work so unusual is the seamless melding of classical structure with deep, romantic expressive feeling. There was palpable excitement as if one stood at the foot of a large waterfall as the blended unity of five players sounded like ten players. By the end of the third movement, there appears nothing more to say, yet the cello poses some questions in the opening of the Finale while the other four instruments begin to pose answers, until they are all in furious and inspired harmonic agreement, a unity that takes one’s breath away.

This performance featured the same personnel as the Simon composition with the addition of Paul Woodiel and Sarah Adams (a founding member of the Cassatt Quartet) on viola whose nimble and intense virtuosity mightily enhanced the inspired frenzy of the other four players who were in top form!

Here was a most interesting program that featured both old and new, producing a rare vintage blend not commonly available in concert venues.