by Kevin T McEneaney

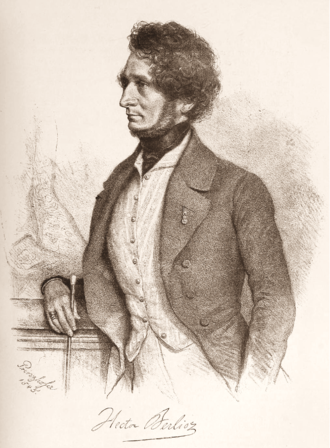

Bard’s Sosnoff Theater with The Orchestra Now presented a peculiar opening for its Valentine’s Day concert which opened with the 1821 Overture of Carl Maria von Weber’s Der Freischütz (The Shooter), Weber’s first international success, which recounts a tragic love story of failed infatuation. This famous and arresting Overture was succeeded by a svelte romantic Piano Concerto by the lesser-known Adolf von Henselt, debuted by Clara Schumann in 1844, and now performed by Evren Ozel. This was followed by Hector Berlioz’s fanciful and amusing Symphonie Fantastique (1830) which concludes with a self-satirizing witches Sabbath. Berlioz was profoundly influenced by Weber (as well as Gluck); Der Freischütz is usually identified as the first Romantic opera, and the biography of Berlioz’ own life bears similarities to the opera. Berlioz adapted and orchestrated Weber’s “Invitation to the Dance” movement from Der Freischütz as a ballet.

The Overture opens so timidly, yet that timidity functions as a foil, for its later fireworks rise in volume, so splendidly delivered by The Orchestra Now with crisp Germanic clarity; the work remains an exciting program summary of the entire opera.

As a young composer Henselt was quite prolific, yet he ceased composing at the age of thirty while continuing to teach; he apparently suffered from stage fright. As a piano performer Henselt was famous for combining Hummel’s smooth textures with Liszt’s explosive sonority. Henselt taught in St. Petersburg; the influence of his style in Russia was as substantial as that of the Irishman John Field. Rachmaninoff considered Henselt to be one of his primary influences. Evren Ozel on piano arrived in a bolt of thunder to let the orchestra know that they were not alone and had to converse with this piano which demanded unusual hand stretches, sudden leaps, and wide-distant chords. This is a minor work that few pianists can manage. As a novelty, it was interesting and often thrilling, yet unlikely to ever be in standard repertoire; an unusual treat to hear it performed, especially the last third movement that made astonishing demands on the pianist. Young Ozel has won a few prestigious international competitions and last year made the quarter finals of the International Chopin Competition in Warsaw. His hands showcased unusual dexterity as well as lightness of touch when engaged in serious conversation with the orchestra.

These works were two early suggestions toward program music, a genre which is closer to Chinese music (although still controversial); The Symphonie Fantastique is full- blown program music with Paganini-like autobiographical clout. The last two movements of opium-induced hallucination-dream were inspired by Thomas DeQuincy’s Confessions of an Opium Addict (1821). The extravagant self-conscious pity of these outlandish movements transforms pathos and self-pity into theatrical comedy with its pulsing rhythms and sudden halts. There is much melodic repetition that rises to exciting, dizzying heights as a result of masterly orchestration. Leon Botstein conducted with much verve and energy.

Berlioz noticed that a large choir of average singers could be superb; he transferred that idea to the orchestra; he originally wanted 130 players in the orchestra but had to settle for 91 at the premiere. Liszt and Berlioz were the great champions of program music that could rise to mountain heights. I hazard the observation that the Symphonie Fantastique in a general aesthetic way had a stimulating influence on the Tragic Overture by Johannes Brahms.

Berlioz’s parody of the medieval dies irae melody in the last movement can bring a broad smile that runs short of laughter. The delirious self-magnification and delusion remain dramatically amusing. Orchestral strings played with demonic fury while percussion supplied heavenly redemption as brass announced final apocalypse. Berlioz’s self-conscious and dramatic ironic edge delights in its everyman quality.

For over 200 years Symphonie Fantastique has enchanted audiences around the globe and will continue to do so, unless we end up living the nightmare of apocalyptic self-destruction, for which there will be no humor.

This article is 666 words: the mark of the Beast (metaphor for Roman Emperor—now Climate Change)!